The blast from the volcano could be heard in Alaska, and the waves crossed the ocean to cause an oil spill and two drownings in Peru. The startling satellite images resembled a massive nuclear explosion.

And yet, despite sitting almost on top of the volcano that erupted so violently on Saturday, the Pacific nation of Tonga appears to have avoided the widespread devastation that many initially feared.

In its first update since the eruption, the government said Tuesday it has confirmed three deaths — two local residents and a British woman. Concerns remain over the fate of people on some of the hard-hit smaller islands, where many houses were destroyed. Communications have been down everywhere, making assessments more difficult.

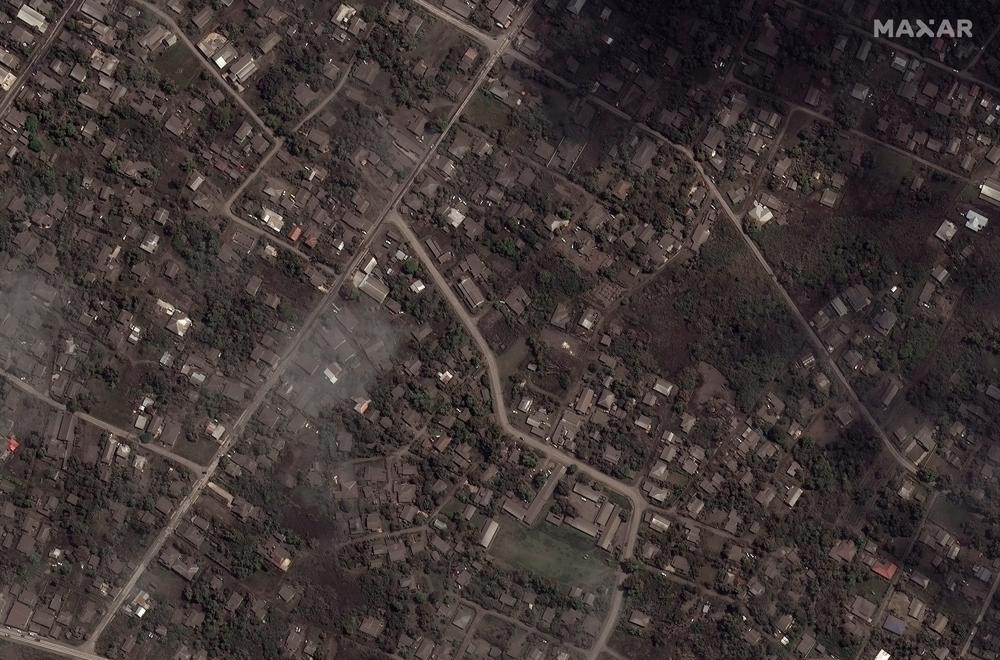

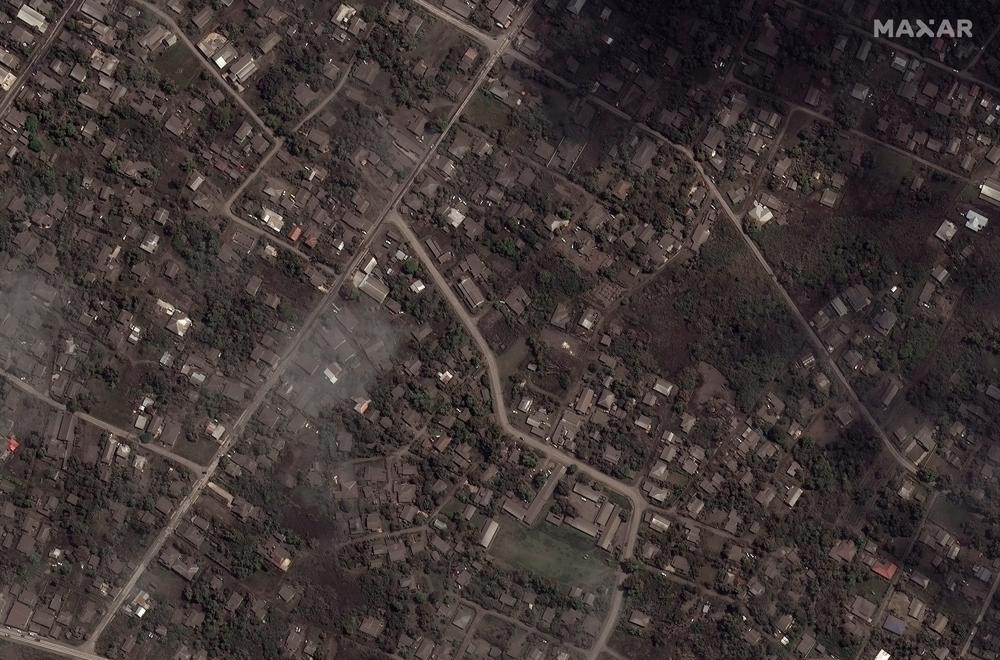

But on Tonga’s main island of Tongatapu, perhaps the biggest problem is the ash that has transformed it into a gray moonscape, contaminating the rainwater that people rely on to drink. New Zealand’s military is sending fresh water and other much-needed supplies, but said Tuesday the ash covering Tonga’s main runway will delay the flight at least another day.

On Tongatapu, at least, life is slowly returning to normal. The tsunami that swept over coastal areas after the eruption was frightening for many but rose only about 80 centimeters (2.7 feet), allowing most to escape.

“We did hold grave fears, given the magnitude of what we saw in that unprecedented blast,” said Katie Greenwood, the head of delegation in the Pacific for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. “Fortunately, in those major population centers we are not seeing the catastrophic effect we thought might happen, and that’s very good news.”

Greenwood, who is based in Fiji and has been talking with people in Tonga by satellite phone, said an estimated 50 homes were destroyed on Tongatapu but that nobody needed to use emergency shelters. She said about 90 people on the nearby island of ’Eua were using shelters.

U.N. humanitarian officials and Tonga’s government reported significant infrastructural damage around Tongatapu and concerns about the lack of contact from some of the low-lying islands. The Geneva-based U.N World Health Organization reported that many people remained unaccounted for.

New Zealand’s High Commission in Tonga also reported significant damage along the western coast of Tongatapu, including to resorts and the waterfront area.

Tonga’s government said all the homes on Mango island — where about 36 people live — were destroyed and only two houses remained standing on Fonoifua island, home to about 69 people.

The government described the event as an “unprecedented disaster” and said tsunami waves had risen as high as 15 meters (49 feet) in places.

Like other island nations in the Pacific, Tonga is regularly exposed to the extremes of nature, whether it be cyclones or earthquakes, making people more resilient to the challenges they bring.

Indeed, Greenwood said Tonga does not want an influx of aid workers following the eruption. Tonga is one of the few remaining places in the world that has managed to avoid any outbreaks of the coronavirus, and officials fear that if outsiders bring in the virus it could create a much bigger disaster than the one they’re already facing.

Another worry, said Greenwood, is that the volcano could erupt again. She said there is currently no working equipment around it which could help predict such an event.

Two people drowned in Peru, which also reported the oil spill after waves moved a ship that was transferring oil at a refinery.

In Tonga, British woman Angela Glover, 50, was one of those who died after being swept away by a wave, her family said.

Nick Eleini said his sister’s body had been found and that her husband survived. “I understand that this terrible accident came about as they tried to rescue their dogs,” Eleini told Sky News. He said it had been his sister’s life dream to live in the South Pacific and “she loved her life there.”

Tonga’s government said a 65-year-old woman on Mango island and a 49-year-old man from Nomuka island had also died, while a number of other people had suffered injuries.

New Zealand’s military said it hoped the airfield in Tonga would be opened either Wednesday or Thursday. The military said it had considered an airdrop but that was “not the preference of the Tongan authorities.”

Jonathan Veitch, the U.N.’s Fiji-based acting resident coordinator for the Pacific islands, said he was hopeful the runway would be operational very soon. And despite damage on the coastline and at the port in Tongatapu, he said, ships should be able to dock.

New Zealand also sent two navy ships to Tonga on Tuesday and pledged an initial 1 million New Zealand dollars ($680,000) toward recovery efforts.

Australia sent a navy ship from Sydney to Brisbane to prepare for a support mission if needed.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian on Tuesday said China is preparing to send drinking water, food, personal protective equipment and other supplies to Tonga as soon as flights resume.

The U.N. World Food Program is exploring how to bring in relief supplies and more staff and has received a request to restore communication lines in Tonga, which is home to about 105,000 people, U.N. spokesman Stephane Dujarric said.

Communications with the island nation are limited because the single underwater fiber-optic cable that connects Tonga to the rest of the world was likely severed in the eruption. The company that owns the cable said the repairs could take weeks.

Samiuela Fonua, who chairs the board at Tonga Cable Ltd., said the cable appeared to have been severed soon after the eruption. He said the cable lies atop and within coral reef, which can be sharp.

Fonua said a ship would need to pull up the cable to assess the damage and then crews would need to fix it. A single break might take a week to repair, he said, while multiple breaks could take up to three weeks. He added that it was unclear when it would be safe for a ship to venture near the undersea volcano to undertake the work.

A second undersea cable that connects the islands within Tonga also appeared to have been severed, Fonua said. However, a local phone network was working, allowing Tongans to call each other. But he said the lingering ash cloud was continuing to make even satellite phone calls abroad difficult.