Hundreds of men, strung out on heroin, opium and meth, were strewn over the hillside overlooking Kabul, some in tents, some lying in the dirt. Dogs skulked around because they sometimes give them drugs, and there were bodies of overdosed dogs amid the garbage. Men here as well slip, quiet and alone, across the line from oblivion and despair to death.

“There’s a dead man next to you,” someone told me as I picked my way among them, taking pictures. “We buried someone over there earlier,” another said further down.

One man lay face down in the mud, unmoving. I shook him by the shoulder and asked if he was alive. He turned his head a bit, just half out of the mud, and whispered that he was.

“You’re dying,” I told him. “Try to survive.”

“It’s fine,” he said, his voice exhausted. “It’s okay to die.”

He lifted his body a little. I gave him some water, and someone gave him a glass pipe of heroin. Smoking it gave him some energy. He said his name was Dawood. He had lost a leg to a mine about a decade ago during the war; after that he couldn’t work, and his life fell apart. He had turned to drugs to escape.

Drug addiction has long been a problem in Afghanistan, the world’s biggest producer of opium and heroin and now a major source of meth. The ranks of the addicted have been fueled by persistent poverty and by decades of war that left few families unscarred.

It appears to only be getting worse since the country’s economy collapsed after the seizure of power by the Taliban in August last year and the subsequent halt of international financing. Families that were once able to get by found their livelihoods cut off, leaving many barely able to afford food. Millions have joined the ranks of the impoverished.

The growing numbers of addicts are found around Kabul, living in parks and sewage drains, under bridges, on open hillsides.

A 2015 survey by the UN estimated that up to 2.3 million people had used drugs that year, which would have amounted to around 5% of the population at the time. Now, seven years later, the number is not known, but it’s believed to have only increased, said the head of the Drug Demand Reduction Department, Dr Zalmel, who like many Afghans uses only one name.

The Taliban, who seized power nearly a year ago, have launched an aggressive campaign to eradicate poppy cultivation. At the same time, they inherited the ousted, internationally backed government’s policy of rounding up addicts and forcing them into camps.

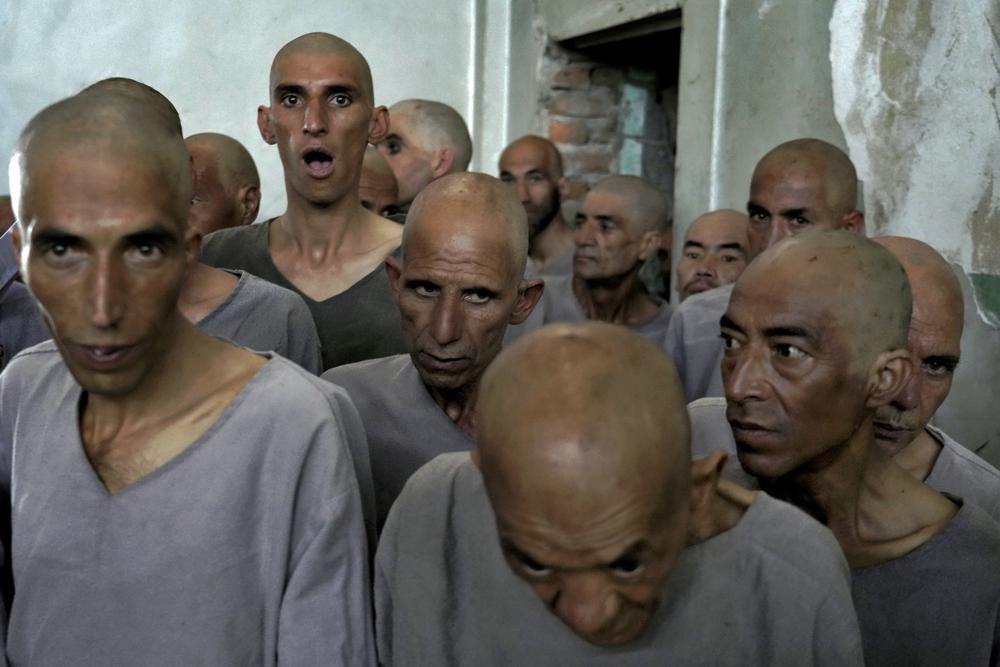

On two nights earlier in the summer, Taliban fighters stormed two areas where addicts gather — the one on the hillside and another under a bridge. In total, they collected some 1,500 people, according to officials in charge of registering them. They were herded into trucks and cars and taken to the Avicenna Medical Hospital for Drug Treatment, a former US military base that in 2016 was converted into a drug treatment center.

It’s the biggest of a number of addict treatment camps around Kabul. There, the addicts were shaved and kept in barracks for 45 days. They receive no treatment or medication as they go through withdrawal. Since the Taliban seizure of power, the international funding on which the Afghan government relied has been cut off, so the camp barely has enough funding to feed its inmate-patients.

But the camps do little to break addiction.

A week after the raids, I went back to both locations, and both were once again full of hundreds of people.

On the hillside, I saw a man who was clearly not an addict. In the darkness, he wandered among the men, shining a feeble flashlight on each. He was searching for his brother, who became addicted years ago and left home. He goes from site to site, through Kabul’s netherworld. “I hope one day I can find him,” he said.

At the site under the bridge, the stench of sewage and garbage was overwhelming. One man, Nazer, in his 30s, seemed to be respected among his fellow addicts; he broke up fights among them and negotiated disputes.

He told me he spends most of his days here under the bridge but goes to his house every once in a while. Addiction has spread throughout his family, he said.

When I expressed surprise that the den under the bridge had filled up again, Nazir gave a smile. “It’s normal,” he said. “Every day, they become more and more ... it never ends.”

An Afghan drug addict smokes heroin on the edge of a hill in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Thursday, June 9, 2022. Drug addiction has long been a problem in Afghanistan, the world’s biggest producer of opium and heroin. The ranks of the addicted have been fueled by persistent poverty and by decades of war that left few families unscarred. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan drug addict smokes heroin on the edge of a hill in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Thursday, June 9, 2022. Drug addiction has long been a problem in Afghanistan, the world’s biggest producer of opium and heroin. The ranks of the addicted have been fueled by persistent poverty and by decades of war that left few families unscarred. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan drug addict smokes heroin on the edge of a hill in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Thursday, June 9, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan drug addict smokes heroin on the edge of a hill in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Thursday, June 9, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan drug addict gives heroin to an addicted dog on the edge of a hill in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Tuesday, June 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan drug addict gives heroin to an addicted dog on the edge of a hill in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Tuesday, June 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Addicted dogs sit among the hundreds of Afghan addicts who gather on the edge of a hill to consume drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Wednesday, June 8, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Addicted dogs sit among the hundreds of Afghan addicts who gather on the edge of a hill to consume drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Wednesday, June 8, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Hundreds of Afghan addicts gather under a bridge to consume drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Wednesday, June 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Hundreds of Afghan addicts gather under a bridge to consume drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Wednesday, June 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan drug addicts gather under a bridge to smoke heroin, as the addicted and hungover dogs have fallen on the ground, in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, June 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan drug addicts gather under a bridge to smoke heroin, as the addicted and hungover dogs have fallen on the ground, in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, June 7, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Hundreds of Afghan addicts gather under a bridge to consume drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Wednesday, June 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Hundreds of Afghan addicts gather under a bridge to consume drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Wednesday, June 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan drug addict smokes heroin on the edge of a hill in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Thursday, June 16, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan drug addict smokes heroin on the edge of a hill in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Thursday, June 16, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan drug addicts gather under a bridge to consume drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan, Thursday, June 9, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan drug addicts gather under a bridge to consume drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan, Thursday, June 9, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan addicts smoke heroin under a bridge in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Thursday, June 9, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan addicts smoke heroin under a bridge in the city of Kabul, Afghanistan,Thursday, June 9, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Body of a dead addict lies covered by a shawl in an area inhabited by drug users under a bridge in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday, June 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Body of a dead addict lies covered by a shawl in an area inhabited by drug users under a bridge in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday, June 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan searches for his drug addicted brother among other addicts under a bridge in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday, June 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

An Afghan searches for his drug addicted brother among other addicts under a bridge in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday, June 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Taliban fighters look for drug addicts hiding in the garbage to detain and move them to a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday, June 1, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Taliban fighters look for drug addicts hiding in the garbage to detain and move them to a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday, June 1, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Taliban fighters look for drug addicts hiding in the garbage to detain and move them to a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday, June 1, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Taliban fighters look for drug addicts hiding in the garbage to detain and move them to a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday, June 1, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan drug addicts who were rounded up during a Taliban raid are waiting in a truck to be taken to a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Thursday, June 2, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan drug addicts who were rounded up during a Taliban raid are waiting in a truck to be taken to a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Thursday, June 2, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan drug addicts who were rounded up during a Taliban raid are waiting in a truck to be taken to a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Thursday, June 2, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Afghan drug addicts who were rounded up during a Taliban raid are waiting in a truck to be taken to a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Thursday, June 2, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid walk in line on their way to the detoxification ward of a drug addiction treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid walk in line on their way to the detoxification ward of a drug addiction treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid wait to have a shower in a drug addiction treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid wait to have a shower in a drug addiction treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid wait to have their heads shaved in a drug addiction treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid wait to have their heads shaved in a drug addiction treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

A drug addict detained during a Taliban raid is shaved at a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

A drug addict detained during a Taliban raid is shaved at a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

A drug addict detained during a Taliban raid is shaved at a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

A drug addict detained during a Taliban raid is shaved at a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Tuesday, May 31, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid wait to be transferred to the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Sunday, May 29, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid wait to be transferred to the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Sunday, May 29, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid, are taken to the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Sunday, May 29, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts detained during a Taliban raid, are taken to the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Sunday, May 29, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

A drug addict sits on his bed in the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Monday, May 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

A drug addict sits on his bed in the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Monday, May 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts rest on their bed in the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Sunday, May 29, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts rest on their bed in the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Sunday, May 29, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts undergoing treatment eat in a dining hall of a drug treatment camp, in Kabul Afghanistan, Monday, May 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts undergoing treatment eat in a dining hall of a drug treatment camp, in Kabul Afghanistan, Monday, May 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts undergoing treatment eat in a dining hall of a drug treatment camp, in Kabul Afghanistan, Monday, May 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts undergoing treatment eat in a dining hall of a drug treatment camp, in Kabul Afghanistan, Monday, May 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts undergoing treatment stand in the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan,Sunday, June 19, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

Drug addicts undergoing treatment stand in the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan,Sunday, June 19, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

A drug addict undergoing treatment looks out from behind the iron bars of the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Monday, May 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)

A drug addict undergoing treatment looks out from behind the iron bars of the detoxification ward of a drug treatment camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, Monday, May 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi/RSS)