Two weeks ago, a 57 -year-old woman and her son were admitted to the COVID ward of APF Hospital, Balambu. The woman's husband had died of COVID-19 just days ago.

Her husband's death made her fear if she would lose her son too. As anxiety increased, her health worsened. She was in dire need of ICU treatment . But she kept on refusing.

The patient said with Dr Kundu Shrestha, who was involved in their treatment, "My son is in the ward. I don't want to leave him."

Dr Shrestha understood it to be a case of 'happy hypoxia' when COVID-19 patients seem to be alright and “happy” despite dangerously low level of oxygen in the blood.

The woman repeatedly asked to stay with her son and be involved in his care. She had no idea about her own health condition which was more critical than her son's. Dr Shrestha was reminding her, "You need ICU treatment. If you are treated in time, we will make you healthy and discharge you with your son."

Her health was deteriorating. Her desire to live was slowly evaporating after death of her husband. She kept on mumbling that she wants to die and be with her dead husband.

Dr Shrestha was trying to convince her in every which way she could. The woman was already suffering from depression. Her willpower to survive was gradually decreasing.

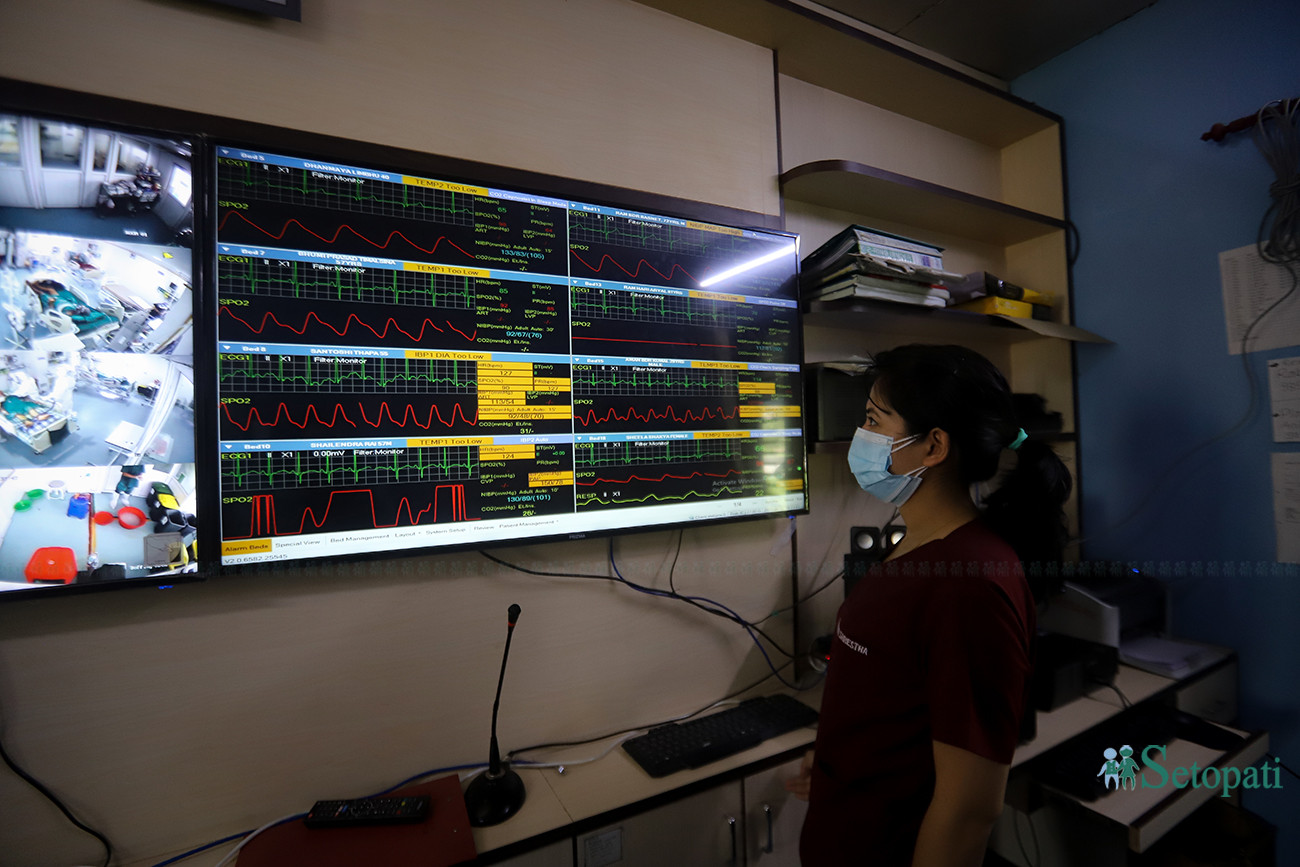

The next day, Dr Shrestha was checking the reports of all the patients in the ICU. Most of the patients' health seemed to have improved. But the woman's was worsening. She was not responding to the requests of medics at the ICU. She was crying. Dr Shrestha was watching all that from the monitoring cameras.

Dr Shrestha had not even had her morning tea. She hurriedly put on a PPE suit and went inside. She was accompanied by other doctors and health workers.

As soon as she entered, she approached the woman and whispered in her ear, "You’re having a hard time, right? Look at me, open your eyes slowly, everything will be fine."

The woman gave a quick look at her but couldn't speak.

As the oxygen level plummeted, they decided to put the woman on a ventilator.

.jpg)

Dr Shrestha called the woman's daughter. "Do whatever you think is right. Her life is in your hands. Save her if you can," the daughter replied in resignation.

Nurses were moving in and out of the door to get the essentials. The woman was given cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for about 45 minutes. There was no response. The team then tried cardioversion, administering of synchronized shock to bring the heart back into operation.

After a while, the dreaded sharp continuous sound of the monitor echoed in the ICU…

The woman did not survive.

.jpg)

"Seems she really wanted to go to the place where her husband is," Dr Shrestha felt. She took a deep breath.

She still had to do the hardest task of informing the woman's daughter.

"We tried our best, but she is no more. We’re sorry."

Dr Shrestha had just finished the conversation, and hospital announcement system blared, "Another patient is arriving at the emergency ward. Get ready"

A team of health workers, including Dr Shrestha, immediately went to attend to the patient.

Dr Shrestha finally came out from the ICU ward at around six in the evening.

The frustration of not being able to save the patient seemed apparent in her eyes. She had left the tea cup after a sip in the morning and now she finally ate a bowl of food. She made a phone call to her husband. As her husband is also a doctor, she could mix medical argot and be expressive. Her husband always consoles her. Boosts her self-esteem.

The next morning, the woman's daughter came to take the body for funeral. Dr Shrestha went to see her. She explained everything.

"I have become an orphan now," the daughter rued.

Dr Shrestha couldn't say anything and still feels the pain.

She did not face as many deaths in the first wave of pandemic as in the second wave. She recalls that most patients recovered in a short time in the first wave.

.jpg)

She has been on ICU duty for 14 hours a day from the very beginning of the second wave.

At some point, the condition of the patient inside would deteriorate when she is just out of the ICU ward. She would have to go inside immediately again.

She would get thirsty while on duty but could not drink water even when her throat is scorched. During menstruation, it is more difficult to go to the toilet. Opening the PPE suit, and putting it back on costs her and her patients a lot of invaluable time.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, thousands of health workers like Dr Shrestha have been living their everyday life leaving their personal space and life.

The pandemic has abated a bit in recent days. Dr Shrestha now gets a week off after a week of duty.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Dr Shrestha, who completed MBBS from Nobel Medical College at the age of 23, initially served at the Patan Hospital. She came to the APF Hospital shortly afterward. She has been a doctor for eight years. She has served in the UN mission in the war-torn region of South Sudan after joining the APF.

"It feels very painful to remember that time. But I learned and understood a lot from the experience of working outside my country," she says.

After returning from Sudan, she specialized in anesthesiology and critical care. She was promoted from the position of inspector to become a DSP.

She was assigned to see COVID-19 patients since the start of pandemic. She started to live with her parents in Kuleshwor, Kathmandu instead of her husband’s house. There are older adults at home and she was afraid of infecting them. Her husband lives in Pokhara studying medicine.

"It has been a year and a half since I've been living in my parents' home," says Dr Shrestha.

She has a mother and father. Many months have passed since she has been physically close to her parents even while living in the same house. She lives on a separate floor.

"What do you need? What do you want to eat? What should we bring?" he parents ask from upstairs.

When she leaves for the hospital, they wave their hands from the veranda. Everything else happens over the phone. They have become accustomed to this routine.

"It's been a long time since we've sit down together to eat. We see each other clearly on video calls. But I don't have any complaint. I am even more proud that my daughter is a doctor," says her father.

Her mother says, "She cries when any patient under her care dies."

Even when Dr Shrestha is home for a week, her mind is always at the ICU ward. She keeps calling her colleagues daily about the health status of the patients under her supervision. She keeps advising.

She remembers them holding her hand like a child. She smiles remembering the warmth.

At some point, she remembers the moment she spoke to a patient who had been on the ventilator for eight days.

Speaking softly after being extubated, the patient had a request, "Please send me a picture showing your face."

"May I know for what reason?" she asked.

"I don't know your face. I have only seen you in this white dress. I want to go out and show everyone your picture and say that this doctor brought me back from death."

When she heard this, her eyes became moist with happiness.

She laughed and said, "When you go out, we both shall sit together and take photos, if it is okay with you."

After that, she sat down to talk with her colleague Dr Anup Bhujel. "We have never tried to understand how it feels for a patient to get out of a ventilator, whether they remember anything or not."

Dr Bhujel said, "Let’s ask the patient once he can speak well."

A few days later, Dr Shrestha asked, "What do you remember of all the days you were on the ventilator?"

"Nothing. But time and again people dressed in white would come near me, hold me," the patient said apparently referring to the medics in PPE suits.

"What do you remember when you regain consciousness?"

"It was very bright. Somebody was telling me that I should get up now, that I slept for too long and now it's time to wake up and walk again. And when I opened my eyes I saw you guys all dressed in white like Gods. I don't know how a God looks like but to me you guys are Gods."

The eyes of Dr Shrestha and her colleagues again became moist on hearing that.