The Political Party Self-evaluation Procedure prepared by the Election Commission has sparked controversy.

The commission had drafted the procedure and sought suggestions from political parties. However, instead of providing written feedback, the parties publicly opposed it, putting the commission in a difficult position.

Let’s first discuss the contents of the procedure prepared by the commission.

The procedure requires political parties to self-evaluate their activities and enter the details into a system (software) designed by the commission. Through such self-evaluation, the commission aims to make the operations of political parties more transparent and accountable.

The commission intends to task parties with evaluating whether they are operating in accordance with the law and whether their internal activities strengthen internal democracy. Additionally, parties are required to assess whether their structures are inclusive and whether their financial status is transparent.

The procedure proposes forming an evaluation committee, led by the Election Commission’s secretary and comprising heads of various divisions, IT section, legal and decision enforcement section, and political party management section of the commission. This committee would be responsible for operating, overseeing, and directing the self-evaluation process.

The committee is also proposed to have the authority to investigate whether parties have conducted self-evaluation and to recommend decisions to the commissioners.

It would assist parties requesting support for self-evaluation, investigate complaints related to evaluation, require parties to appoint a contact person for self-evaluation, ensure self-evaluation reports are submitted to the commission within three months of the fiscal year’s end, and make them public.

Currently, political parties submit written details to the Election Commission during party mergers or splits. However, the procedure mandates that details of party registration, mergers, or splits be entered into the software within six months, and financial audit reports be uploaded within 35 days of completion of the audit.

The procedure also requires parties to maintain records of assets (cash and in-kind), vehicles, representation in the National Assembly, House of Representatives, and local levels, as well as gender and inclusion-related statistics, the number of candidates fielded in elections, and records of votes received under the proportional representation system.

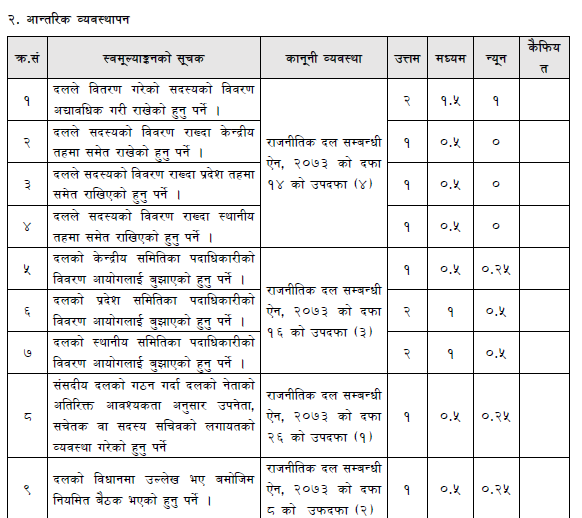

The procedure proposes assigning scores based on actions such as disclosing income and expenditure, party accounts, and sources of contributions exceeding Rs 100,000. Scores would also be based on gender and inclusion for office-bearers appointed in party structures, from the central committee to lower levels, requiring at least one-third female representation in the system.

Parties would receive scores based on whether elections for office-bearers at the federal and provincial levels are held every five years. Those failing to hold conventions on time will receive lower scores.

For example, parties are required to report whether they hold regular meetings as per their statutes, with different scores for those that do and that don’t.

Parties would also receive different scores based on whether they take action against individuals violating the code of conduct or not.

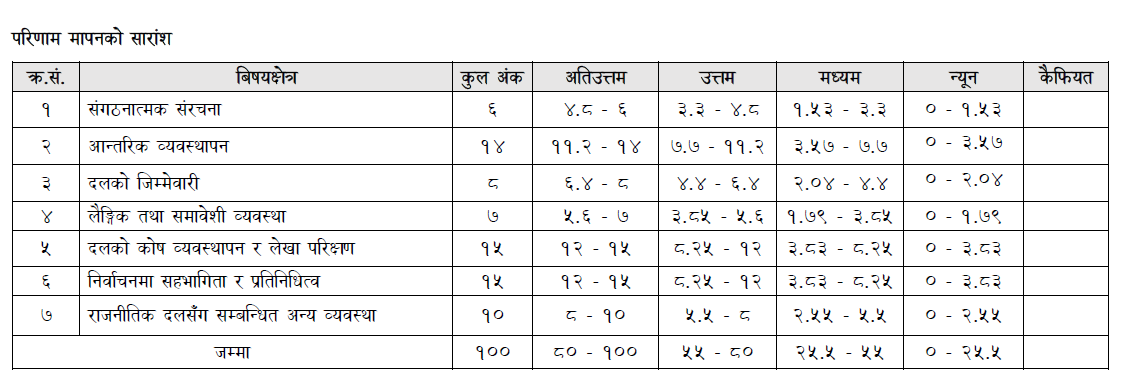

Based on this self-evaluation scoring system, the Election Commission has allocated a total of 100 points. Parties scoring 80–100 would be deemed excellent, 55–80 good, 25–55 average, and below 25 poor.

The commission also proposes training for individuals from political parties responsible for uploading data to the software. If a party fails to submit details to the system, its name would be published on the commission’s website and through the media.

Ten parties, including the CPN (Maoist Center), Rastriya Swatantra Party, and Rastriya Prajatantra Party, issued a joint statement opposing this procedure.

They objected to the provision allowing a secretary-led committee to evaluate, operate, oversee, and direct political parties. They also argued that, while the procedure is based on the Political Parties Act, it grants the commission excessive authority beyond what federal law allows, and that the procedure’s scoring system intends to restrict political freedom.

Nepali Congress General Secretary Bishwa Prakash Sharma also opposed the procedure, stating on social media platform X: “Political parties are evaluated by the public and directed by the Constitution. We clearly disagree with the draft of the Political Party Self-evaluation Procedure 2082. Let this be resolved through legal means at Bahadur Bhawan.” (Bahadur Bhawan refers to the Election Commission’s central office in Kantipath, Kathmandu.)

When asked why the NC opposed the procedure, Sharma said that he had already expressed his views on social media.

The Election Commission, however, is perplexed as parties have opposed the procedure instead of providing suggestions.

Ram Prasad Bhandari, the acting chief election commissioner, said that the draft of the procedure was prepared based on past suggestions from parties.

“Discussions on the self-evaluation procedure had been taking place for the past four years, and we also have minutes of the discussions with parties,” he said. “The procedure hasn’t been enforced yet; parties were asked to study it and offer suggestions.”

Bhandari expressed surprise at the outright opposition to the entire procedure by parties instead of specific suggestions on what to retain or remove. He noted that the procedure was developed based on experiences from other countries, and that 32 parties participated in discussions during its formulation.

He said that a committee led by former chief secretary Tirtha Man Shakya drafted the procedure.

“Neither have we encroached on parties’ jurisdiction, nor made a decision,” Bhandari said. “The commission is authorized to formulate election-related laws and procedures.”

He clarified that the commission isn’t trying to monitor parties’ internal democracy or operations but is asking them to self-evaluate their activities to stay connected with the public.

Bhandari urged parties to collaborate with the commission to revise the procedure. He added that the commission can’t force the parties if they are not interested.

Another election commissioner said that parties are opposing the procedure because they don’t want transparency.

“The commission wants parties to hold timely events, conventions, maintain financial transparency, and evaluate themselves based on these actions,” the commissioner said. “As parties have not held general conventions for years, not formed departments as per their statutes, and not fielded candidates for gender representation at local levels, they are opposing the procedure as they would receive scores based on this through self-evaluation.”

The commission has asked parties to give scores to themselves based on 75 indicators. It has clearly specified which provisions of the Political Parties Act the indicators are based on.

“Section 16 (1) of the Political Parties Act contains the provision requiring elections for office-bearers to be held every five years. Parties holding conventions every five years receive 2 points, while those holding delayed conventions get 1 point. This means parties will receive points for holding timely conventions. Where is the commission interfering?” the commissioner said.

As parties have opposed the procedure outright instead of engaging in debate, the procedure is not likely to be implemented immediately, the commissioner added.