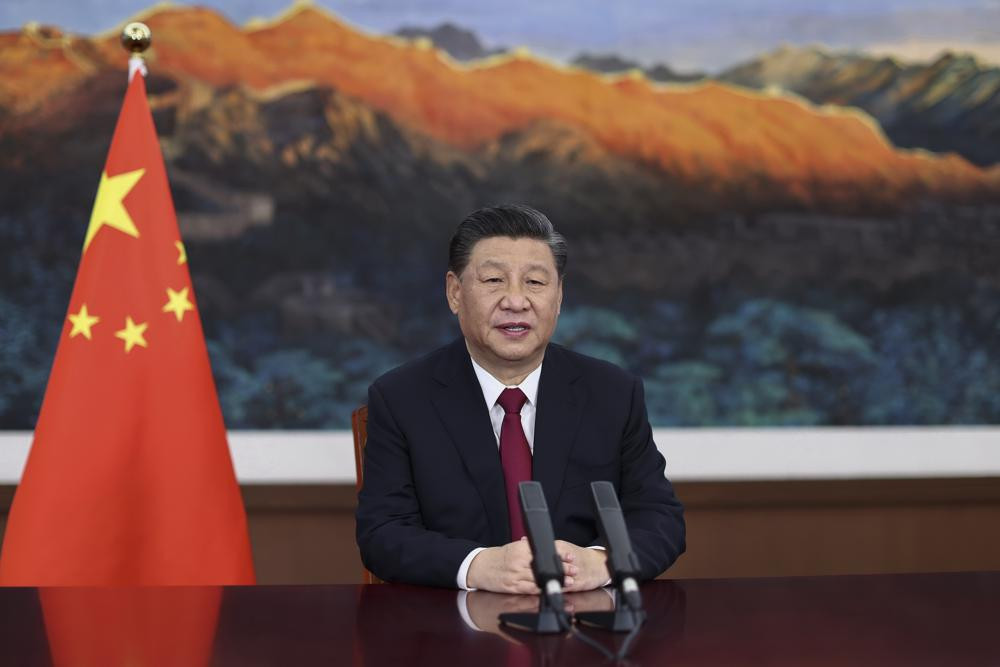

Chinese leader Xi Jinping emerged from a party conclave this week not only more firmly ensconced in power than ever, but also with a stronger ideological and theoretical grasp on the ruling Communist Party’s past, present and future. That lays the groundwork for him to take a third five-year term as party leader at next year’s national congress, elevating to the likes of Mao Zedong, who founded the People’s Republic in 1949, and Deng Xiaoping, who opened up the economy three decades later.

A look at some of the meaning behind the recent developments.

WHAT’S THE SIGNIFANCE OF XI’S ELEVATION?

Though the rules were unwritten, Xi’s two immediate predecessors served just two terms as head of the party in keeping with term limits on the presidency. Xi, 68, had the constitution amended, however, to eliminate presidential term limits and could therefore remain in office until he dies, steps down or is forced out.

Though he is the son of a former high official, a friend to both Mao and Deng, Xi rose to the pinnacle by applying what is now referred to as the hybrid economic theory of “socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era.” Though not new, Xi has made it one of his standards, alongside his call for the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” and the “Chinese dream” of relative prosperity.

Key to realizing those goals are the “two centenaries,” namely building a “relatively prosperous society” by the party’s 2021 centenary, which it claims to have achieved, and a “modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious” by the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949.

All such terms aim to project the image that the party under Xi has engineered a system that adapts to the times and delivers on its citizens’ desire for better quality of life for themselves and their families, and greater respect for China in the international community.

WHAT DID THE MEETING DO FOR XI?

Although already named the “core leader,” Xi gains further cachet from such phrases’ inclusion in the resolution issued Thursday by the party’s Central Committee on historical questions concerning the party over the past 100 years. That was only the third such document issued by the party; the first was in 1945 under Mao, the second in 1981 under Deng. To wield such authority in the eyes of party historians and theoreticians certainly makes Xi one of the most dominant Chinese figures of the century.

Naturally, only positive achievements are mentioned. While extolling the party’s successes, the resolution glosses over less flattering periods such as the massive famine and industrial failure of the Great Leap Forward in the late ’50s and early ’60s, the chaotic 1966-76 Cultural Revolution and the political upheaval of the 1989 student-led pro-democracy movement in Beijing that was crushed by the army.

WHAT WAS THE MEETING’S PURPOSE?

Like all meetings of the 95 million-member party’s Central Committee of 400 or so top officials, the gathering aimed to achieve unity of thinking and unity of purpose. Heavy on ceremony it featured Xi seated center stage in an enormous room in the Great Hall of the People in the heart of Beijing. The party holds roughly seven such gatherings between each of its national congresses, which are held once every five years.

“By firmly supporting and upholding General Secretary Xi’s core position, the whole party will have an anchor, the entire Chinese people will have a backbone and the giant vessel of China’s rejuvenation will have a steady hand on the helm,” Jiang Jinquan, director of the Central Committee’s Policy Research Office, told reporters at a Friday briefing. “No matter what choppy waves we might encounter, we will always be able to stay calm and composed.”

While Xi is almost certain to remain head of the party after next year’s congress, likely to be held around November, it’s not clear how many of the other six members of the Politburo Standing Committee — the apex of political power in China — will stay on. Premier Li Keqiang, the party’s No. 2 after Xi, meets the age criteria to remain, although such rules allow for a certain amount of flexibility.

WHAT CHALLENGES DOES XI FACE NEXT?

Xi faces no political rivals at home, but he does face a difficult economic situation and China’s “zero tolerance” approach toward COVID-19 has yet to stamp-out the outbreak while taking a toll on many people’s personal and financial lives. China’s economy is also heavily dependent on housing sales and construction, and a major slump in the industry is causing jitters, chilling auto and retail sales. Financial markets are on edge about whether one of the biggest developers, Evergrande Group, might be allowed to collapse under 2 trillion yuan ($310 billion) in debt as a warning to others.

Economic strategy has been sometimes contradictory since Xi took power in 2012. The party promises to make the economy more open and competitive. At the same time, it is building up state-owned “national champions” that dominate banking, oil and other industries while also tightening control over private sector tech giants that are China’s biggest success stories of the past three decades.

Abroad, Xi has pushed a bold line, with the government angrily dismissing complaints about issues from his signature “Belt-and-Road” infrastructure initiative, to human rights, the sharp curtailing of rights in Hong Kong and mass detentions and other abuses against Uyghurs and members of other Muslim minority groups in the northwestern region of Xinjiang. Relations with the U.S. are especially tense amid disputes over trade, technology and China’s threats against Taiwan, the self-governing island that Xi has vowed to bring under Chinese control at a time that some analysts believe is growing increasingly near.

“Under the strong leadership of the party’s central committee with comrade Xi Jinping as the core, we will rally the entire party like a piece of unbreakable iron and march forward in lockstep,” Qu Qingshan, director of the Institute of Party History and Literature, said at Friday’s briefing.