Dozens of doctors and nurses silently lined the hospital hallway in tribute: For a history-making two months, a pig’s kidney worked normally inside the brain-dead man on the gurney rolling past them.

The dramatic experiment came to an end Wednesday as surgeons at NYU Langone Health removed the pig kidney and returned the donated body of Maurice “Mo” Miller to his family for cremation.

It marked the longest a genetically modified pig kidney has ever functioned inside a human, albeit a deceased one. And by pushing the boundaries of research with the dead, the scientists learned critical lessons they’re preparing to share with the Food and Drug Administration -– in hopes of eventually testing pig kidneys in the living.

“It’s a combination of excitement and relief,” Dr. Robert Montgomery, the transplant surgeon who led the experiment, told The Associated Press. “Two months is a lot to have a pig kidney in this good a condition. That gives you a lot of confidence” for next attempts.

Montgomery, himself a recipient of a heart transplant, sees animal-to-human transplants as crucial to ease the nation’s organ shortage. More than 100,000 people are on the national waiting list, most who need a kidney, and thousands will die waiting.

So-called xenotransplantation attempts have failed for decades — the human immune system immediately destroyed foreign animal tissue. What’s new: Trying pigs genetically modified so their organs are more humanlike.

Some short experiments in deceased bodies avoided an immediate immune attack but shed no light on a more common form of rejection that can take a month to form. Last year, University of Maryland surgeons tried to save a dying man with a pig heart –- but he survived only two months as the organ failed for reasons that aren’t completely clear. And the FDA gave Montgomery’s team a list of questions about how pig organs really perform their jobs compared to human ones.

Montgomery gambled that maintaining Miller’s body on a ventilator for two months to see how the pig kidney worked could answer some of those questions.

“I’m so proud of you,” Miller’s sister, Mary Miller-Duffy, said in a tearful farewell at her brother’s bedside this week.

Miller had collapsed and was declared brain-dead, unable to donate his organs because of cancer. After wrestling with the choice, Miller-Duffy donated the Newburgh, New York, man’s body for the pig experiment. She recently got a card from a stranger in California who’s awaiting a kidney transplant, thanking her for helping to move forward desperately needed research.

“This has been quite the journey,” Miller-Duffy said as she and her wife Sue Duffy hugged Montgomery’s team.

On July 14, shortly before his 58th birthday, surgeons replaced Miller’s own kidneys with one pig kidney plus the animal’s thymus, a gland that trains immune cells. For the first month, the kidney worked with no signs of trouble.

But soon after, doctors measured a slight decrease in the amount of urine produced. A biopsy confirmed a subtle sign that rejection was beginning –- giving doctors an opportunity to tell if it was treatable. Sure enough, the kidney’s performance bounced back with a change in standard immune-suppressing medicines that patients use today.

“We are learning that this is actually doable,” said NYU transplant immunologist Massimo Mangiola.

The researchers checked off other FDA questions, including seeing no differences in how the pig kidney reacted to human hormones, excreted antibiotics or experienced medicine-related side effects.

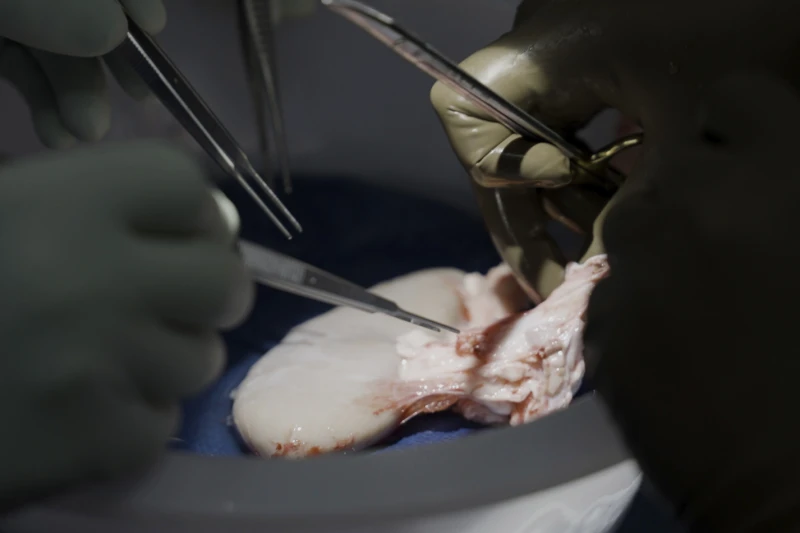

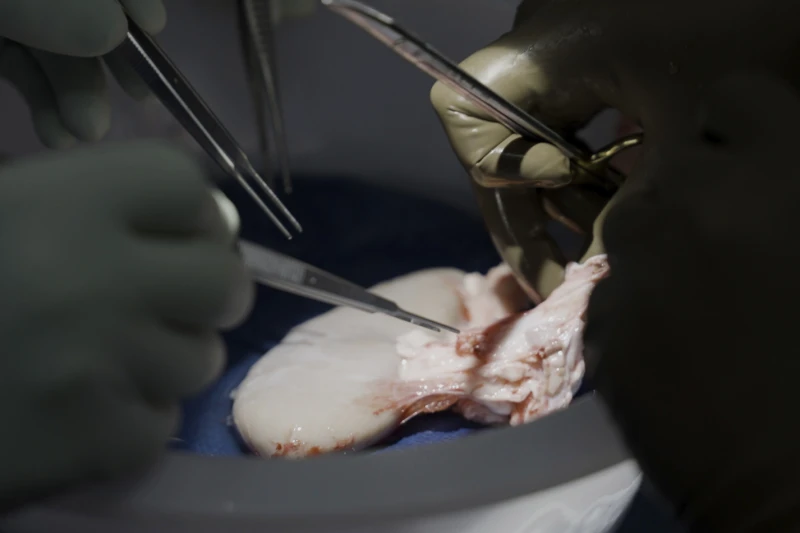

“It looks beautiful, it’s exactly the way normal kidneys look,” Dr. Jeffrey Stern said Wednesday after removing the pig kidney at the 61-day mark for closer examination.

The next steps: Researchers took about 180 different tissue samples –- from every major organ, lymph nodes, the digestive tract –- to scour for any hints of problems due to the xenotransplant.

Experiments in the deceased cannot predict that the organs will work the same in the living, cautioned Karen Maschke, a research scholar at the Hastings Center who is helping develop ethics and policy recommendations for xenotransplant clinical trials.

But they can provide other valuable information, she said. That includes helping to tease out differences between pigs with up to 10 genetics changes that some research teams prefer — and those like Montgomery uses that have just a single change, removal of a gene that triggers an immediate immune attack.

“Why we’re doing this is because there are a lot of people that unfortunately die before having the opportunity of a second chance at life,” said Mangiola, the immunologist. “And we need to do something about it.”