Dive into any media or social media platforms frequented by the Nepali audience, what hits you first and last? You’re guessing right, it's the content on politics, politics, and more politics! Right behind that, you’ll find the buzz of “viral content,” revolving around trending controversies that capture public attention with surprising speed, becoming the talk of the town from bustling tea stalls to the halls of Parliament.

It seems everyone, from the general public to policymakers, and from kindergarten classrooms to university lecture halls, is swept up in the frenzy of these sizzling topics. This type of content is contagious; one day, a topic can dominate the discourse, only to be replaced by another the next.

Picture this: a snazzy podcast setup with high-quality cameras, and a settee where naive artists or self-proclaimed activists in their twenties opine passionately on political absurdities and societal norms. Or in other scenes, with a microphone in hand, often wielded in a vigilante style, an impassioned youth challenges authorities with everyday politics, while simultaneously hunting for the next piece of “viral content.” Or a gentleman with a classy “YouTube setup” and a self-proclaimed “subversive media messiah” armed with half-baked facts, provoking the public with political outrage on non-issues while also riding on the latest trend.

Common to all is the “politics” and “viral content,” the two exquisite art forms that truly unite Nepalis in the quest for endless scrolling and catastrophizing. This raises a question: In a nation overflowing with political discourse and viral content, are we losing sight of more pressing issues that deserve our focus?

Absolutely! Agriculture, which once engaged 80 percent of the population and fueled three-quarters of our economy, is now shrinking down to just two-thirds of the population and contributing a mere one-fifth to our GDP.

Recently, several credible news outlets have begun highlighting the dire situation of off-season and untimely droughts in the Tarai-Madhes region. Suddenly, “Madhes sukkhagrasta” (Dry Madhes) became the buzzword and is echoing through the public sphere, causing a stir among the public, politicians, and policymakers alike. But do these brouhaha-loving individuals know that these fields used to get seasonally puddled in the past?

Agriculture in Nepal has suffered from cyclical drought and inundations, which technicians commonly refer to as “water stress.” It isn’t just about wet and dry spells; it encompasses the unpredictable and uneven patterns of rainfall that arrive when they are least needed. Just a few years ago, post-monsoon deluges devastated ready-to-harvest crops in the western regions of the country. Even last year, torrential rains wreaked havoc, destroying a significant portion of agricultural production.

Now, let’s dive into the buzz surrounding this summer's drought and the looming agro-apocalypse that grips the nation. A few months back, the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) circulated reports about above-average monsoon expectations. It seems that many simply adopted a “business as usual” mentality, failing to consider the “what ifs.”

But here’s the kicker: it wasn’t just policymakers and government authorities who remained oblivious; the public, too, seemed to brush off the potential challenges ahead. After all, we know the government often goes into a kind of hibernation, even in the face of clear disaster calls. Just recall their delayed responses to the Nakkhu flooding or the Simaltal landslide. Instead of taking proactive measures, our authorities often intervene only after a disaster strikes, offering temporary fixes rather than sustainable solutions, but that’s a conversation for another time!

Returning to the drought: summer droughts have become a global crisis, and agriculture bears the brunt of this unfolding disaster. In the EU, summer droughts resulted in a staggering loss of billions in agriculture, with projections suggesting even greater impacts in the years to come. This phenomenon is not isolated; it resonates globally, hitting agricultural sectors hard across different regions. When such turmoil is added to the fragile value chains of economies, it paves the way for inflation, ultimately threatening global food security.

In the context of Nepal, summer drought is not a new suffering but rather a recurring issue that has been largely neglected in the past. Historically, the country faced these challenges in 1992 and 2015. Local drought (I refer to this term here as the unavailability of the right amount of water at the right time for crops) is a common occurrence in most parts of the agrarian areas. Even in regions equipped with substantial irrigation infrastructure, the highland areas often rely solely on rain, making them particularly vulnerable to dry spells.

While the economic repercussions of drought on agriculture in Nepal have yet to be comprehensively quantified in independent studies, they are frequently subsumed under broader narratives of climate change. A report by the OECD underscored this concern, suggesting that global crop yields could plummet by as much as 22 percent.

Additionally, I have not had access to the comprehensive nationwide survey results specifically addressing the impact of drought on crop yields in Nepal; however, my background as an agricultural irrigation engineer has provided me with valuable insights. During my work on the Babai Irrigation Project, I conducted detailed crop cut surveys for rice, examining the command area of both branch and sub-branch canal systems as well as the surrounding areas.

The average yield in areas with a sufficient water supply was recorded at 4 tons per hectare, significantly higher than the national average. In contrast, the tail end of the canal system yielded an average of 3.5 tons per hectare, while upland areas without canal irrigation yielded only 2.6 tons per hectare, representing an approximate 35 percent reduction.

Although these findings cannot be universally applied to every condition or farming system throughout Nepal, they do underscore the critical impact of water scarcity on agricultural yield. As rice serves as the nation's staple crop, its vulnerability to fluctuations in water availability is particularly alarming. With Nepal’s rice productivity already trailing behind the global and South Asian averages, the potential ramifications of continued water deprivation are indeed staggering.

The southern plains (Tarai-Madhes) are referred to as the "breadbasket" and serve as the agricultural backbone of Nepal, sustaining approximately two-thirds of the nation’s population in terms of food security. The prolonged delay in rice cropping due to persistent drought conditions has captured the attention of the public, media, and policymakers alike.

In response to this escalating crisis, the provincial government of Madhes has officially classified the region as drought-prone, a designation subsequently endorsed by the federal government, declaring it a drought-hit zone. Along with the immediate relief packages by all three tiers of government, the prime minister has conducted an aerial inspection of the affected areas and announced the initiation of 500 deep borewell drilling (deep boring) projects as a countermeasure. However, the salient question remains: are such interventions sufficient, or are they merely reactive measures to a deeper systemic issue?

Despite Madhes being heralded as the emblematic region of crisis, the food security challenges faced by the remaining one-third of the population engaging in small-scale farming across the hills and valleys have largely evaded attention. Anecdotal conversations with my family and local networks in the eastern hills reveal a disconcerting trend: an escalation of drought conditions.

Furthermore, a manual analysis of social media discourse, particularly on X (formerly Twitter), underscores a mounting anxiety among users who report analogous drought-related incidents in both the mid and western hills. This frenzy surrounding the "viral" trend has obscured the pressing crisis unfolding in the hills.

This highlights an urgent need to go beyond the trend and conduct a systematic and comprehensive study across the entire country, paving the way for targeted interventions that address the unique challenges faced.

What do we have on hand?

A. Water availability and harnessing

When it comes to water resources, Nepal is far from barren. As outlined in the Water Resources Policy of 2020, the nation boasts an impressive annual water potential of 225 billion cubic meters (BCM), with a significant portion attributed to groundwater (12 BCM). This positions Nepal as one of the most water-abundant countries in South Asia.

The major river catchments are Koshi, Gandaki, Karnali, and Mahakali, and the approximate catchment area of the country is 191,000 square kilometers (with portions extending into neighboring China and India). The utilization of these resources has been extensive, expanding from eastern to western Nepal, with an irrigated command area totaling approximately 887,750 hectares, with large-scale irrigation systems mostly concentrated in the Tarai-Madhes region.

Among the standout irrigation projects are Sunsari Morang (68,000 hectares), Bagmati Irrigation (45,600 hectares), Sikta (42,000 hectares), Babai (36,000+ hectares), Rani Jamara (38,300 hectares), and Mahakali (45,120 hectares).

Besides, there have been significant strides in groundwater extraction through deep borewells in the plains, lift irrigation in riparian uplands, for enhancing agricultural water supply. The country is also home to a multitude of farmer-managed irrigation systems (FMIS), which effectively service smaller command areas and promote localized management of water resources.

Additionally, Nepal has been actively engaged in the development of trans-basin irrigation initiatives. Noteworthy projects currently in progress include the Bheri-Babai Diversion and the Sunkoshi Marine Diversion. Future projects on the docket, such as the Kaligandaki-Tinau and Tamor-Chisang diversions, exemplify a strategic approach to resource management aimed at improving the country’s irrigation framework.

Furthermore, each subcatchment in Nepal presents unique geological and topographical characteristics that could facilitate sub-basin water transfers, presenting opportunities for optimized water distribution. Agricultural lands exceeding 10 hectares have been earmarked as targeted intervention zones for irrigation enhancements, laying the groundwork for progressive initiatives by agricultural and irrigation authorities.

In summary, Nepal boasts abundant water resources with considerable potential for sustainable agricultural utilization through innovative irrigation solutions.

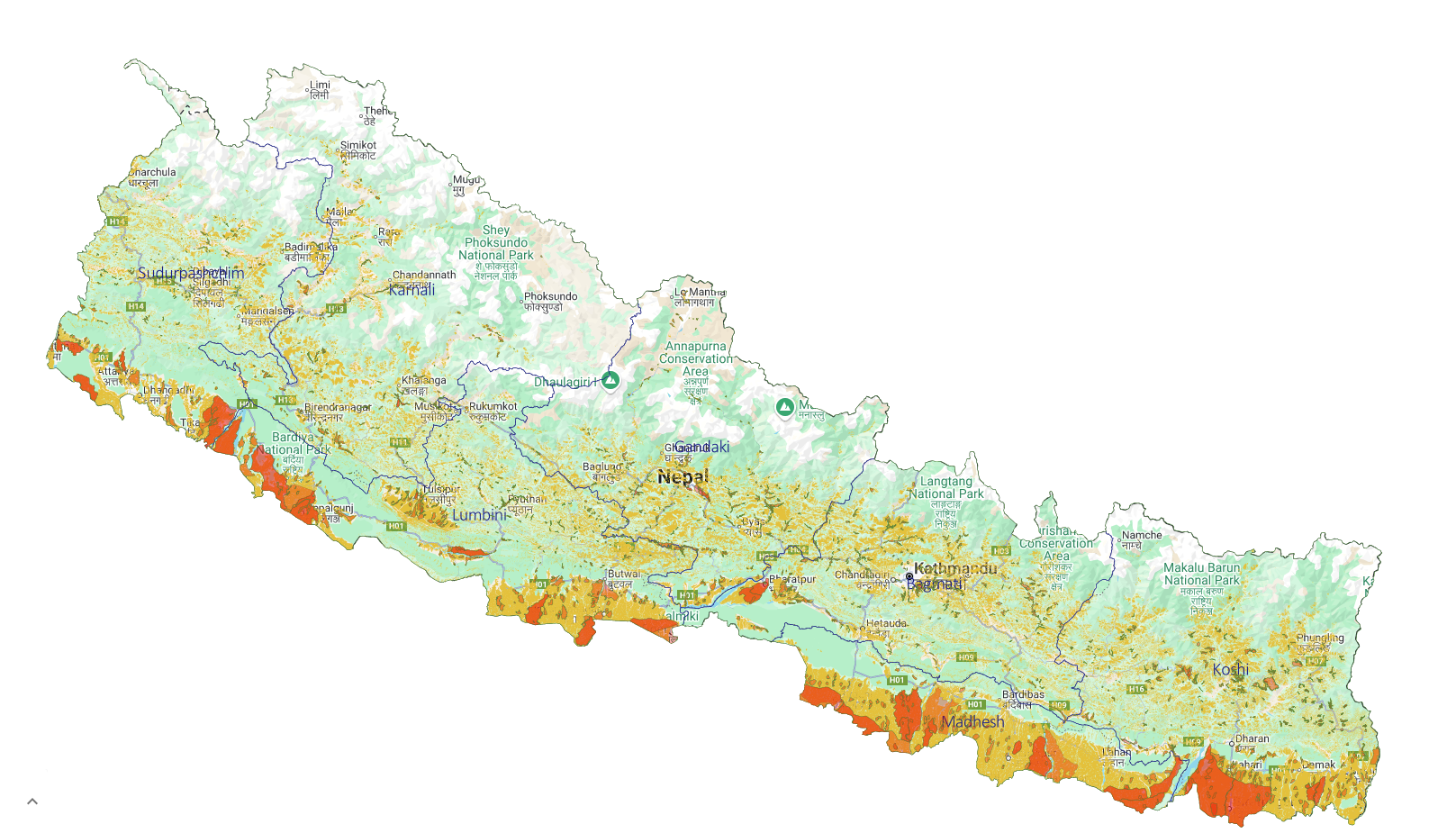

Total irrigated area in Nepal (Source: Nepal Irrigation Management Information System)

Total irrigated area in Nepal (Source: Nepal Irrigation Management Information System)

B. Policies, acts, regulations, and plans

In the realm of water resource management and agricultural policy, a complex tapestry of legislation and strategic frameworks exists, often leading to contention and contradictions among various directives.

Key legislative instruments include the Water Resources Act (1992), the Agricultural Perspective Plan (APP) (1995), the Irrigation Policy (2003), the Agriculture Policy (2004), the Water Resources Strategy (2002), the National Water Plan (2005), etc. (A detailed summary for water can be explored in Water Sector Policies and Guidelines of Nepal or from the website of Nepal Law Commission).

Collectively, these policies aim to regulate, manage, and exploit water resources; however, they frequently impose significant constraints within the sector. The focus on stringent regulation tends to obscure the practical responsibilities of institutions, leading to inefficiencies and operational challenges.

In addressing water-induced hazards, a plethora of policies is activated, including the Natural Calamity (Relief) Act (1982), the Environmental Protection Act (1996), the National Action Plan on Disaster Reduction (1996), the National Disaster Response Framework (2013), the Water-Induced Disaster Management Policy (2015), the National Climate Change Policy (2019), the National Agricultural Policy (2004) etc.

This extensive array of regulations continues to grow as agriculture is closely linked to three commodities: water, soil, and society.

C. Institutional arrangements

Across the spectrum of governance from federal to local levels, a myriad of institutions are dedicated to advancing agriculture, irrigation, water management, infrastructure, and disaster prevention in Nepal.

At the federal level, key players include the Ministry (with their respective departments) of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation; the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development; the Ministry of Forests and Environment; the Ministry of Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation; and the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport. Additionally, the Ministry of Home Affairs plays a pivotal role in disaster preparedness and management, ensuring a coordinated response to emergent situations.

At the provincial level, each infrastructure ministry (otherwise mentioned) maintains dedicated units to implement policies and programs pertinent to agriculture and water resource management. Every district is equipped with either division or subdivision offices for agriculture, water resources, and irrigation, staffed with thousands of engineers, agricultural experts, and social mobilizers.

Local bodies, through their divisions of infrastructure development, contribute significantly to enhancing agricultural productivity.

Each year, substantial budgets are allocated across this three-tiered structure to bolster efforts in these sectors. Furthermore, a substantial amount of funding is allocated through various international organizations. Some of them include the World Vision, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), Mercy Corps, the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), etc. All of these collectively play a crucial role in supporting agricultural development and enhancing irrigation and water management practices throughout the country.

In addition to these institutional endeavors, focused initiatives like the Presidential Chure Conservation Program, Prime Minister’s Agricultural Modernization Programs, etc., add further dimensions to the agricultural framework.

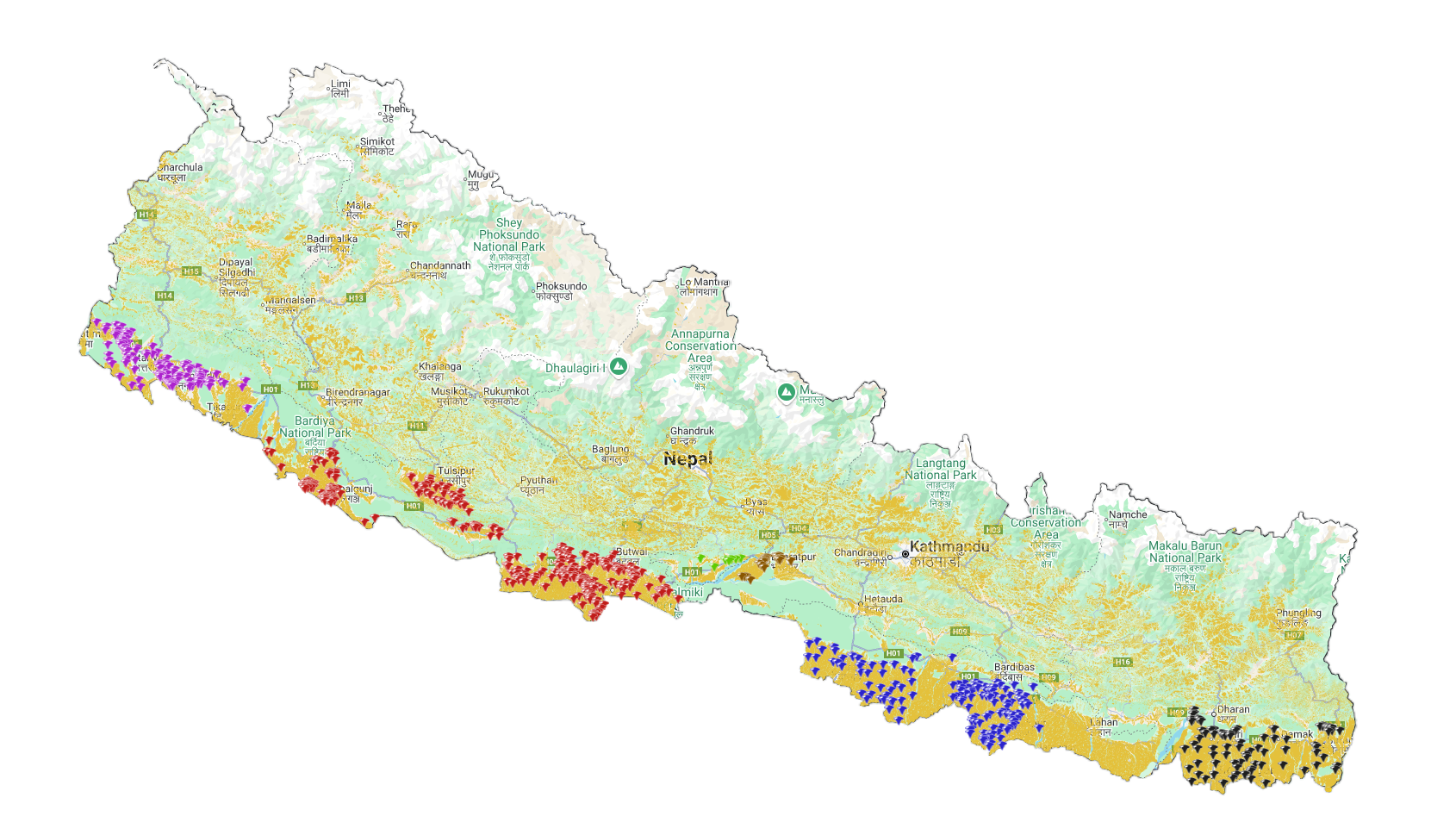

Large-scale groundwater projects in Nepal (Source: Nepal Irrigation Management Information System)

Large-scale groundwater projects in Nepal (Source: Nepal Irrigation Management Information System)

Despite the robust institutional architecture and resource allocation, challenges persist, disasters continue to evoke significant concern, agricultural productivity remains low, and cyclical disasters often go unmitigated.

One might wonder: Why?

The grim tales begin with the perceived mentality of “jasto chha chaldai janchha” (It is what it is, and life just goes on) and not questioning why or why not. From the very beginning, we have resoundingly heard of Nepal as “jalsrot ko dhani desh (a country rich in water resources)” while witnessing the pressing realities faced by its populace.

We saw many individuals laboriously toting jerrycans and gagros (traditional water containers) over long distances to secure water for domestic use. We saw farmers waiting for the entire cropping season, in the stillness post-midnight, anticipating their turn to wrestle with the whims of irrigation. Never asked why.

We saw the cultural expression in songs like “Gairikhet ko sirai hanyo barsha yam ko Daraundi le” but never inquired about the specter of water-induced disasters looming over agricultural land. We always witnessed the fluctuating rice price and blissfully accepted the “mahango chamal” (costly rice) during Dashain (main festival), but never questioned why.

OK! Why this “Kolaveri Di?”

The answer is hidden within the maxim "too many cooks spoil the broth." Effective resource harnessing demands judicious decision-making; yet we find ourselves ensnared in a labyrinth of governance dysfunction that stifles progress.

The optimal use of water resources is ensnared in a cyclical trap of paper policies, fragmented authorities, political bargaining, and institutional inertia, severely impeding substantive progress. The current approach of intervention is predominantly budget-driven, often prioritizing power dynamics over empirical evidence or hydrological insights. Allocations are shaped less by actual needs or sustainability imperatives and more by the competing interests of politicians at various levels of governance. This creates a policy quagmire characterized by circular accountability, procedural redundancies, and a lack of coordination among overlapping institutions.

In the absence of robust research to inform decision-making and lacking a cohesive strategy to align disparate interests, the system perpetuates a bureaucratic loop. Consequently, not only is natural water scarcity exacerbated, but governance failures also produce artificial droughts, situations where, despite physical water availability, governance mechanisms falter.

Furthermore, the intertwining of red and green tape, where bureaucratic obstacles and environmental approvals are either misapplied or inconsistently enforced, exacerbates delays and inefficiencies. Such procedural bottlenecks enable a culture of “business as usual” to prevail, allowing critical areas requiring urgent focus to languish.

In response to cyclical environmental crises such as droughts, floods, or agricultural failures, a predictable cycle of reactive measures surfaces, prompting temporary responses rather than systemic reform. This reactionary mindset reinforces a pattern where crises serve as the sole catalysts for engagement, leaving underlying causes obscured amid bureaucratic delays, fragmented governance, and politicized priorities.

What is the way forward?

Long-term strategies

The point of departure for proper resource management necessitates a paradigm shift from entrenched institutional inertia toward a holistic approach that prioritizes research-driven, context-specific, and equity-focused water governance.

While significant advancements have been made in resource identification, as evidenced by the aggregation of data on accessible platforms, a critical gap remains in establishing institutional memory. This is essential for documenting interventions made at all levels of government, enabling a more informed management strategy. Such an inventory system will not only facilitate resource identification and management but also help mitigate the risk of project duplication across different tiers of government.

Additionally, developing a comprehensive institutional memory of resources will enable more contextualized approaches to specific issues, moving away from blanket solutions.

Regarding policy frameworks, these should be grounded in research, realism, and context-specific objectives rather than relying on generalistic perspectives. Generalistic interpretations often lead to implementation challenges and create confusion among stakeholders.

To improve water governance coherence, policies need to unify water management goals with those of agriculture, environment, and socio-economic development, while breaking down silos that cause fragmented efforts. This requires current policy upgrades to ensure they are adaptable, based on scientific evidence, and capable of incorporating local contexts through ongoing monitoring and feedback systems.

Strengthening inter- and intra-governmental coordination is pivotal. This entails establishing clearly defined roles, accountability frameworks, and collaborative platforms to overcome fragmentation and eliminate redundant efforts across the three governance tiers. Establishing inter-ministerial and intergovernmental coordination bodies with clear mandates will enhance synchronized planning, budgeting, and implementation.

Equally important is ensuring that budget allocations are driven by hydrological feasibility and socio-environmental priorities rather than political expediency.

In response to institutional overburden and accountability gaps, a significant institutional reform is required. This reform should focus not on manpower and budget allocations but on the scope of work necessary for effective management.

For instance, the jurisdiction over large irrigation projects should be centralized under the federal government, supported by interdisciplinary teams. Currently, the departments of agriculture and water resources lack coordination, as they operate under separate ministries, thereby hindering the implementation of holistic measures.

The regulatory and implementation framework should be simplified and actionable, facilitating rather than obstructing the implementation of plans and projects.

Given the current policies and frameworks in place, there is a risk that the recent initiative announced by the prime minister concerning deep-borehole drilling will encounter substantial delays, potentially extending over several months, and may not be operational within this fiscal year.

Efforts must be made to dismantle bureaucratic red tape by streamlining robust procedures while maintaining transparency and environmental integrity. Investments in real-time data systems, participatory planning mechanisms, and leveraging local knowledge are critical for fostering adaptive management that is both proactive and responsive to shifts in hydrological conditions.

Fundamentally, transitioning from a reactive crisis management approach to a proactive long-term resilience planning model is vital in cultivating sustainable and equitable water governance.

Immediate actions

There are no immediate solutions for drought, particularly in countries with inadequate infrastructure. However, developed nations have access to certain technological measures that can help. These include the use of chemicals such as enhanced water retainers, remote sensing technologies, and other advancements.

Additionally, improving existing ponds and lakes to create constructed wetlands, utilizing resilient crops, and adjusting crop calendars are viable strategies.

To find sustainable solutions to the impacts of drought, it is essential to monitor its severity and effects. This requires the installation of soil moisture sensors and data loggers. Immediate action is necessary to implement this technology.

For this, deploying interns and thesis students to affected areas to study the impacts and severity of drought can provide valuable insights and support government policies promoting student employment opportunities.

One of the most effective immediate physical measures is to store water, either on the surface or underground. This approach also promotes groundwater recharge through effective catchment protection.

Concluding remarks

In numerous instances, our disaster response strategies have primarily relied on an infrastructural approach. For instance, in addressing the current buzzing “drought in Madhes,” the prime minister announced 500 deep borehole drilling projects, where there are already thousands of such infrastructures (see the figure). Such measures are insufficient and are likely to impose unnecessary financial burdens on taxpayers without yielding substantive results.

Effective solutions require a comprehensive diagnosis of the root causes of the challenges, whether they stem from declining rainfall, over-exploitation of groundwater, lowering of groundwater tables due to geological conditions, capture of resources by the powerful, or any underlying causes.

Addressing these issues mandates a nuanced, case-by-case assessment of the most affected aquifers, rather than relying solely on blanket infrastructural solutions that may offer only temporary respite, leading to another hue and cry in the coming years.

Additionally, following the “viral” trend to address this issue may exacerbate regional disparities, thereby fueling social protests.

A national strategy that considers the multifaceted nature of drought across the country is imperative. Adopting a one-size-fits-all approach will likely strain resources further, and the elite (power) capture of interventions may centralize benefits in select areas, leaving the most vulnerable populations unaddressed.

Therefore, prioritizing rigorous scientific and socio-economic research is crucial in identifying the core issues and facilitating the formulation of targeted, effective strategies. For instance, in the Nordic regions, we have conducted a scientific study on drought management, which is initiating pilot projects exploring smart drainage management systems aimed at alleviating summer droughts.

Besides this, it is crucial to recognize that we share catchments with neighboring countries. In matters of transboundary water issues, our focus has predominantly been on surface water sharing, often neglecting the complexities surrounding transboundary aquifers.

We share a substantial 1,751 kilometers of plain land with India, with nearly every meter potentially harboring valuable groundwater resources. This situation warrants timely discussions on transboundary aquifers framed within the context of “water diplomacy” rather than merely administrative diplomacy.

Importantly, as freshwater resources dwindle, Nepal must reconceptualize its stance on water, recognizing it when and where it is considered as "social good," "economic good," and "human right." This redefinition is crucial for promoting equitable access and sustainable management of shared water resources, ensuring that the needs of all stakeholders are met amid a growing crisis.

As the discourse is mostly driven by “viral trends” and politics, there is a risk that, after a few rain events, the urgency of this situation will dissipate and become just a tale from the past. Instead of getting lost in transient discussions driven by sensationalism, we must confront the underlying issues that demand our genuine attention.

Today, we face drought conditions, but we may soon encounter challenges such as post-monsoon inundation, early winter flooding, and late winter dry spells. The Meteorological Department, as previously mentioned, has faltered in its predictive capabilities, providing no widespread updates; in the future, it must be held accountable for real-time assessments and more accurate forecasting.

Make agriculture the talk of the town; viral content may change daily, but without adequate food resources, the narrative shifts to hunger and remains forever. This drought is merely the precursor to more significant challenges ahead, marking the onset of what can be termed an “Agrocalypse.”

The implications of our current situation are profound, and as we say, “picture abhi baki hai, mere dost” (the story isn’t over yet, my friend). It is crucial for us to shift our gaze from the fleeting allure of viral trends back to the sustainable development of such critical sectors. Rather than merely reacting to the latest headlines, we must engage in more in-depth conversations about the issues that truly impact our society’s well-being and future.

(The author is a doctoral researcher on sustainable water management at the University of Oulu, Finland.)