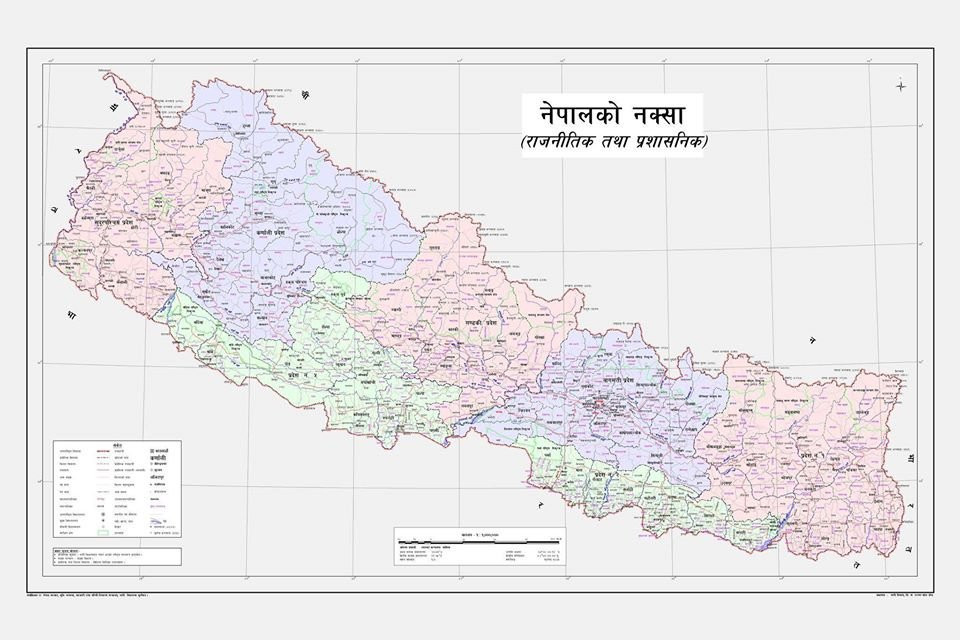

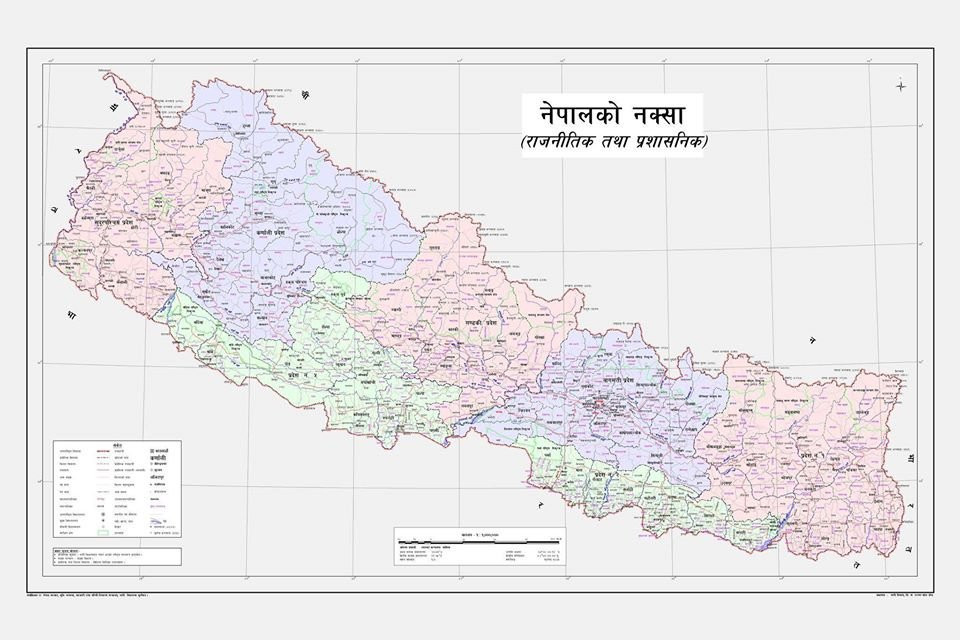

I was born in a rural village in Nepal about 100 kilometers west of the Indian state of West Bengal. As a teenager, I grew up harboring a very strong anti-Indian sentiment. When I was 14 in grade 8, I read in my history books that the East-India Company and Nepal signed a treaty in 1816 to end the Anglo-Nepalese War. And as a result of that treaty, Nepal had to lose one-third of its territory to British India.

I also kept hearing that after the British left India, the two countries signed a treaty of Peace and Friendship which is unequal. I was very unhappy with India as a teenager and used to write poems against India to rid myself of my anger.

A vengeful mentality was growing in my mind and it got magnified each time there was any political tension between Nepal and India. When I travelled to several parts of the world for my study and work, I always wanted to keep a distance from Indians.

But there wasn’t a single country where I did not find an Indian. To avoid sharing a room during conferences and summer programs, I used to write to the organizers in advance requesting not to put me in the same room with an Indian participant, and I would avoid a conversation with them as much as possible. This remained a habit for a long time.

In April 2015 our Himalayan nation was devastated by a deadly M7.8 earthquake which killed around 9000 people leaving several thousands wounded. The earthquake also destroyed infrastructure that was very costly for a nation crawling, weak and struggling after a decade-long Maoist armed conflict that ended in 2006.

In this difficult situation, the people of Nepal had to go through another tragedy. The landlocked nation endured several months of unofficial blockade from its closest neighbor, India. During this time, I was studying in Norway and used to video-call my sisters who were living in Kathmandu. They would cry and say there is nothing to cook, no gas, and other essentials. I would open the news portals to read that there is a shortage of medicine and oxygen in the hospital. An ambulance couldn’t run because there was no fuel. Nepal was on the brink of a great humanitarian crisis.

The Nepali in me was boiling, I became very angry, and in that anger, I wished for the destruction of India.

I introduce myself as a student of peacebuilding. One of the things I reflect on every day is that I must be at peace to understand why there is so much trouble in the world. I realized that I am not at peace at all because of my hate toward India. To me to dislike India meant I was an enemy to all 1.3 billion Indians. The wound was deep, and the hurt was heavy.

I decided that I must attempt to find some answers to this hatred. This thought kept hitting me round the clock. I could not resist anymore and in 2016, I finally bought a flight ticket to Tamil Nadu, India. I decided not to stay at any hotel. I searched and found that there is a spiritual community at Tiruvannamalai around Ramana Ashram and I stayed with a family there for a month. I biked to different villages nearby and met with anybody I came across. Some of them didn’t know that there is a country called Nepal. It was a sign to me that there is so much to experience in life.

During this visit to India, I travelled to six states in three months. Since I mostly stayed with the same community, I quickly became “famous” as a new member wherever I went. It happened often that I was invited by different families for meals.

Once I accepted an invitation to the home of a very poor family. As I entered, I was greeted by the hosts with their three children. I was given rice and several curries with some fish and was asked that I should eat first. I did not feel comfortable eating alone. However, there is this in our culture that says Atithi Devo Bhava, which means The Guest is God.

So I decided to start eating. I could sense that the kids were also asking for food but I guessed that the mother was signaling them to wait. As I finished eating, I was directed to the place where I could wash my hands. On my way back, I looked at the kitchen part of the room and saw that there was almost no food left in the containers. As I paused there for a moment, I felt very bad. I felt a wave of realization passing through my body.

That was a uniquely transformative experience. That family didn’t know that there is a country called Nepal and to them, I was just a guest and they wanted to feed me with special food when they did not have enough for themselves. I felt ashamed of my ignorance and my hatred of the people whom I didn’t know and who didn’t know me. It was a powerful experience.

I felt like everything stopped in front of me as I, in that instant, became friends with each of 1.3 billion Indians all at once for the rest of my life. I come from the land where the Buddha was born and I have read him saying, “Hatred cannot be ceased by hatred at any time. Hatred ceases by love.” This was the first time I experienced it for myself. Now, how do I share this peace, oneness, and friendships in words?

Fortunately for me, I met a community at Panchgani, India, where a global centre of Initiatives of Change has been built. There I listened to several individuals who were able to contribute much more to society after experiencing change in their own life. I found it safe here to share my story. I am now in my third year of participating in this community of changemakers, learning, and growing every moment.

While travelling with the IofC outreach team, I have attempted to share this experience with thousands of individuals and hundreds of organizations in Nepal and India. I get mixed responses. While many relate and resonate with it, some stretch their eyes in disbelief as if to say I am stupid.

Some of my friends in Nepal remind me that I am confused and mixing the Indian people with the Indian government, its foreign policy, etc. But my inner voice tells me that I am not confused, that I am being courageous. I no longer see the need to spit venom on the Indian government to prove that I am a Nepali. We can be creative and help one another in finding peaceful and friendlier means to resolve our conflicts.

My understanding is that our governments are part of us, nothing but all of us individuals put together. In that way, we are all connected. We need to learn to choose the right people to lead us in a better direction and not divide us to cover up their shortcomings. We, as the people from the two countries, can consciously befriend and work as a team toward a greater regional harmony instead of getting consumed by hatred and fear which is only destroying us.

We tend to point fingers at our neighbors, not looking at more fingers pointing back at us. What have we done to the Dalit communities at home in Nepal for centuries? How have we treated our Madheshi brothers and sisters in the plains so that they feel second-class citizens in their own land? Haven’t we humiliated ethnic and religious minorities in Nepal with our sick majority-mentality? Can we learn from COVID- 19 pandemic that isolation is painful and ostracization is a crime?

We must take a holistic look at our motives and behavior to establish a perspective based on accuracy, respect, and inclusion.

I see how I had become a part of these social evils unconsciously by just watching and not doing anything, thinking I am too small to affect change. I must be part of a solution. Equity and justice are the fabrics of humanity and social change is possible only with individual practice. If all of us start to see where we need to change as individuals, we are only one generation away from the just and hate-free society that we always talk about.