NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg has caused a stir with his remarks in a June 17 interview that NATO may deploy more nuclear weapons in response to the growing threat from Russia and China.

“I won’t go into operational details about how many nuclear warheads should be operational and which should be stored, but we need to consult on these issues,” he said.

The day after, at a press conference in Washington, Stoltenberg warned of the threat posed by the renewed partnership between China and Russia.

“If China truly cares about ending the (Ukraine) war, as it claims, it must stop fueling Russia's war machine,” he said.

Harsh statements, but unsurprising given that the Sino-Russian strategic relationship is one of the reasons behind NATO's creation.

Korea and the Cold War

In 1950, the Soviet Union and the newly established People’s Republic of China signed the Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Aid. This treaty was a geopolitical earthquake for the international balance of power – just a few months later North Korea, backed by Moscow and Beijing, invaded the US-supported South.

This Sino-Soviet alliance, coupled with the Korean conflict, dramatically heightened the West’s fear of Communism, prompting the Atlantic Alliance to remilitarize and evolve into a fully-fledged organization (NATO).

The strategic theatres of Europe and the Asia-Pacific became united, making the potential for multiple fronts in containing global Communist expansion a reality for the West. The Sino-Soviet alliance turned into a strategic nightmare for the US and ‘free world’ countries.

Despite its initial impact, the alliance was short-lived, crumbling by the late 1950s. But after the Cold War ended in 1989, NATO expansion prompted Russia to again partner with China, culminating in the bilateral Treaty of Friendship signed in 2001, the core of a potential Eurasian security system.

The 2014 Ukraine crisis further cemented Sino-Russian cooperation, solidifying their image as a combined security challenge to the West-led order in the eyes of NATO and the US.

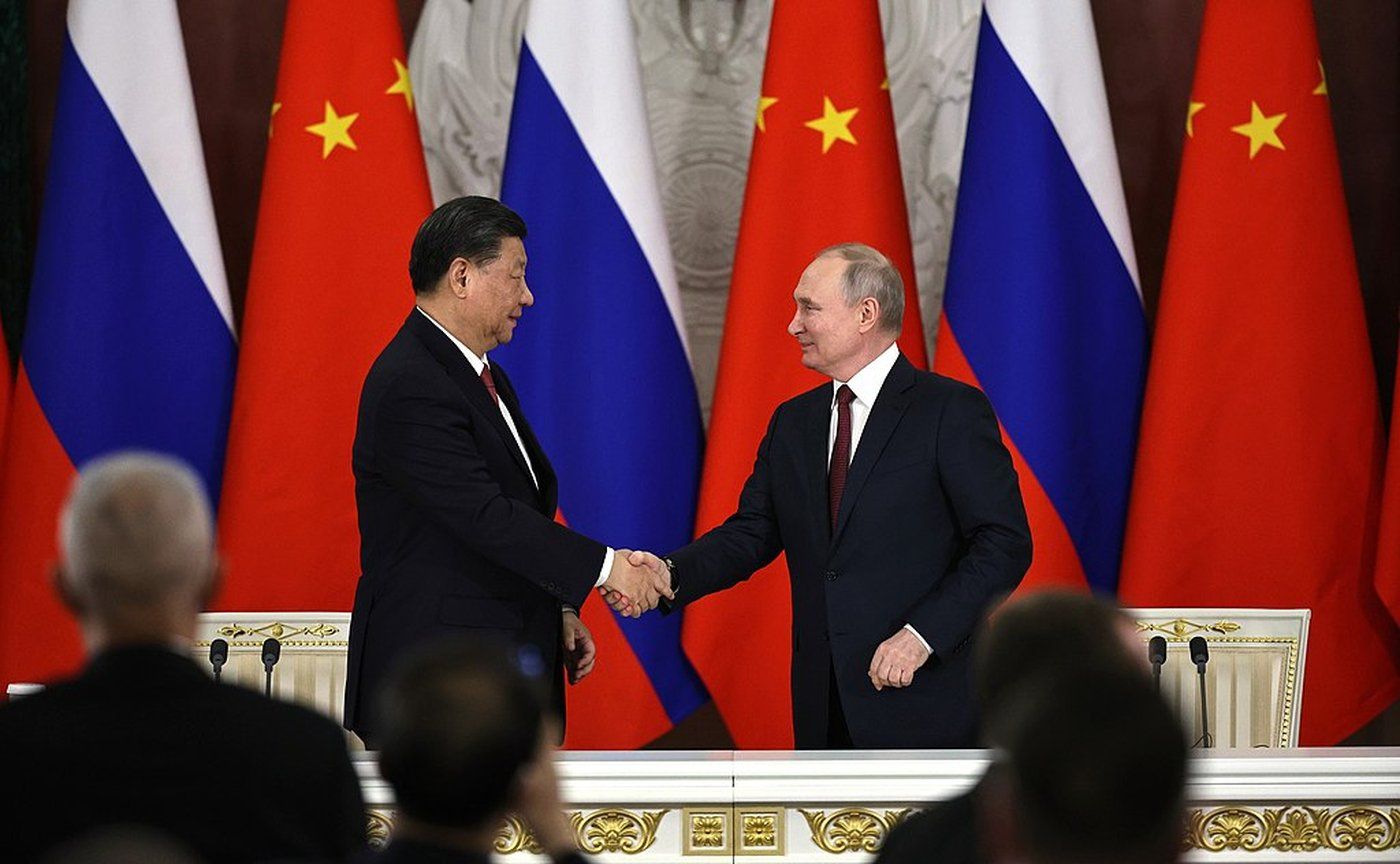

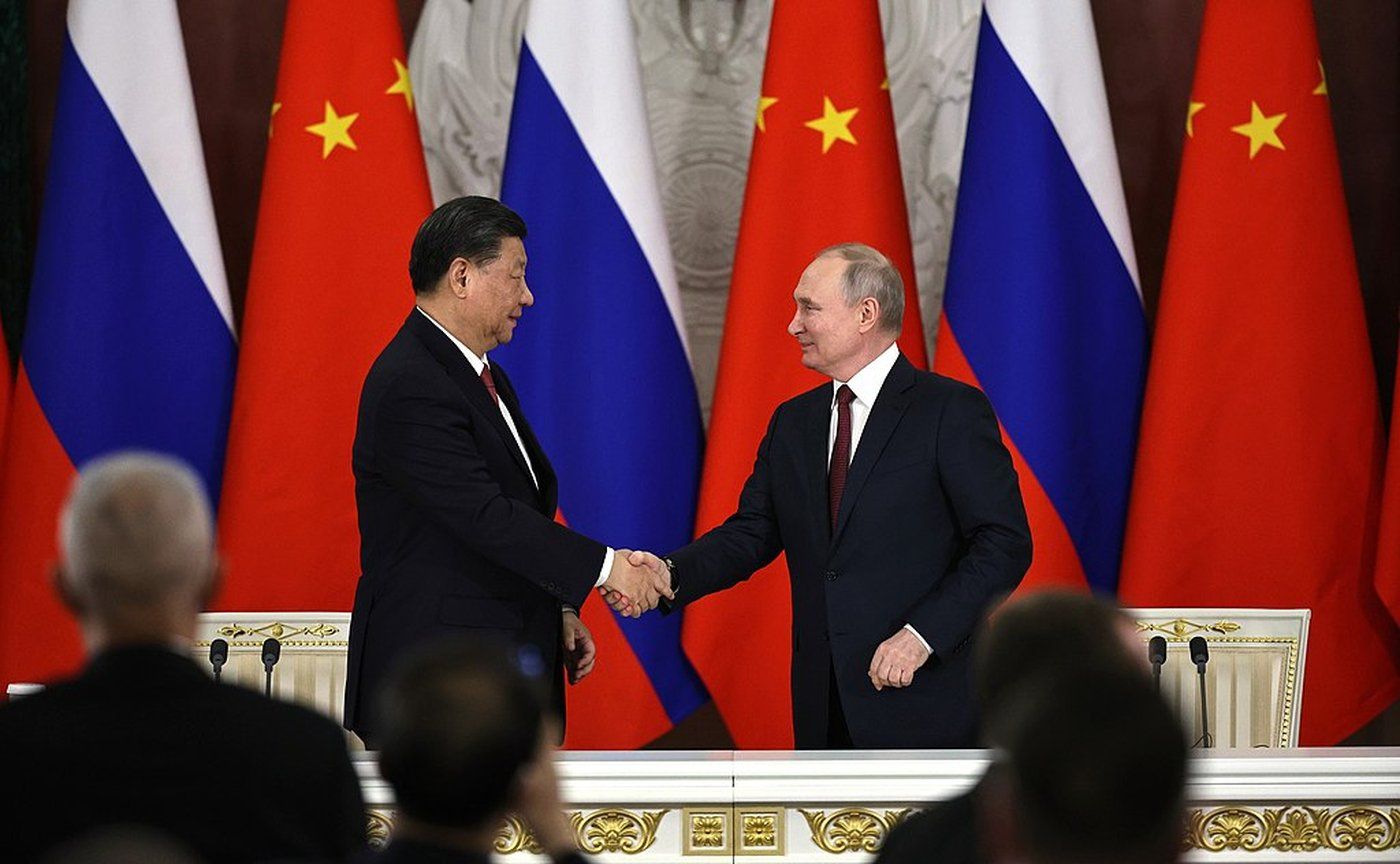

The Joint Statement signed in 2022, on the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, apparently signaled a long-term turning point. Beijing and Moscow pledged that their friendship in the form of “bilateral strategic cooperation” had “no limits”.

They condemned Western countries, primarily NATO, for their ideological approach to international politics.

“The sides oppose further enlargement of NATO and call on the North Atlantic Alliance to abandon its ideologized Cold War approaches, respect the sovereignty, security, and interests of other countries, and exercise a fair and objective attitude towards the peaceful development of other states,” the document read. It’s still unclear whether this declaration pre-dated Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with Chinese assent.

Why the West is worried

The West is increasingly worried about the potential strengthening of strategic ties between China and Russia, with the US expressing the greatest concern.

According to the National Security Strategy released by the Trump administration in 2017, China and Russia are described as “revisionist powers” actively competing against the United States and its allies. The document asserts that both nations aim to reshape the global order in ways contrary to US “values and interests”.

China is highlighted for spreading aspects of its “authoritarian system”, and building a highly “capable and well-funded military”, second only to the US. Its nuclear arsenal is also noted as growing and diversifying.

Russia is seen as aiming to weaken US influence globally, divide it from its allies, and view NATO and the European Union as threats. The document concludes that “great power competition” has returned, with China and Russia reasserting their influence both regionally and globally, challenging American geopolitical advantages and attempting to alter the international order in their favor.

The Biden administration’s 2022 National Security Strategic Guidance echoed these concerns, emphasizing that China and Russia are both geopolitical rivals and ideological competitors.

It described the two countries as “antagonistic authoritarian powers” increasingly challenging democratic nations. The document stated that “authoritarianism is on the global march,” calling for alliances with like-minded nations to revitalize democracy worldwide.

It highlighted that China has become more assertive, positioning itself as the main rival, while Russia remains focused on enhancing its global influence and playing a disruptive role.

To counter the expansion of Sino-Russian authoritarian influence, the document stressed the need to strengthen relationships with democratic allies based on shared ideology, asserting that democratic alliances enable the US to present a united front, produce a unified vision, and promote effective international rules to hold China and Russia accountable.

NATO allies gradually adopted a similar perspective.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Hong Kong autonomy issue in 2020, which led the British government to declare a breach of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, seemingly proved that China does not intend to act as a responsible stakeholder in the current international system.

This intent was also evident in China's refusal to cooperate with the World Health Organization to investigate the origins of the coronavirus that caused COVID-19.

The Ukrainian crisis, which erupted into open war in 2022 with Putin's violation of the Budapest Memorandum, signed in 1994, through the use of force against Ukraine's borders, demonstrated that Russian revisionism has evolved into an overt military threat to European stability and territorial integrity.

NATO's new strategy

NATO recently adopted its new Strategic Concept, emphasizing the need for the allies to adapt to a more demanding strategic environment characterized by the return of systemic rivalry, persistently aggressive Russia, and the rise of China.

According to the document, NATO critically needs political convergence because the scale of threats has significant implications for the security and prosperity of everyone.

The current Western political climate tends to view the Sino-Russian relationship through an ideological lens, seeing the two authoritarian powers as threats to democracy.

China and Russia quickly embraced this perspective, seeking to catalyze political support to create an alternative bloc to Western-style democracies embodied by NATO.

On the one hand, the rise of China on the international stage and Russia’s resurgence as a great power are significantly challenging the global balance of power and posing considerable dilemmas for the Western world.

Over the past two decades, Moscow and Beijing have indeed grown closer, fueled by a shared belief that the West disregards their interests.

In the last 10 years, Russia’s perception that its westward geopolitical ambitions were compromised led it to pivot east, where China was particularly eager to strengthen ties (but not endlessly).

Has a new Cold War begun?

Many US and European leaders argue that a new Cold War has begun.

NATO has taken steps to address this transregional problem, despite China’s geographic position outside its traditional ‘jurisdiction’.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered an understandable NATO rearmament, reminiscent of the Korean War response, but also indicating the resurgence of apparent Cold War-era dynamics.

However, Western political leaders should be cautious in conflating ideological issues with strategic problems.

The Cold War had unique characteristics that can hardly be repeated, and today the situation should not be interpreted through an outdated lens.

The claim that China and Russia have a limitless partnership has been seemingly contradicted by the type of assistance Beijing has provided to Moscow since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, especially when compared to the “unprecedented levels of support” provided by NATO to Kyiv.

Predicting the future remains uncertain, but Western political leaders must consider historical complexities when developing new policies.

Key questions include whether the current global order accurately reflects the real balance of power, whether Beijing and Moscow genuinely share long-term interests because of their (supposed) common ideology, and whether timely diplomatic actions by the US and its Western allies could weaken what many perceive as an authoritarian monolith.

These questions are critical for the future evolution of the international system, and history provides some guidance.

(The author is a Researcher and Lecturer in History of International Relations at the Catholic University of Milan. This article was originally published under Creative Commons by 360info)