Leonard Thompson was 14 when he made history. The Canadian teenager was on his deathbed, drifting in and out of a coma in a Toronto hospital in 1922, when he became the first person to receive an insulin injection to treat diabetes.

It worked. Leonard lived for another 13 years. Insulin became the mass-produced, go-to treatment for millions suffering a disease that had been identified by the ancient Greeks but until then had no effective treatment.

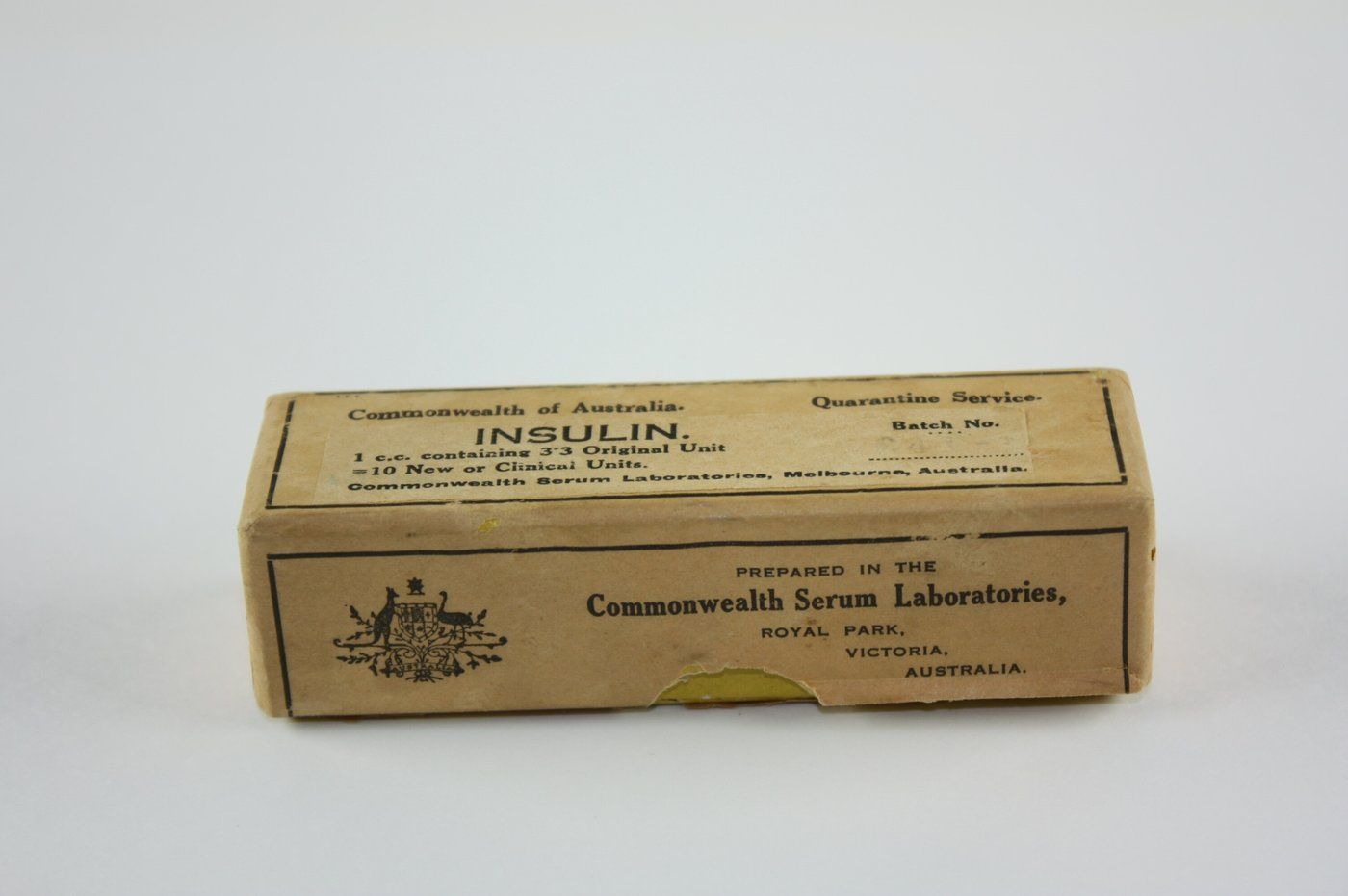

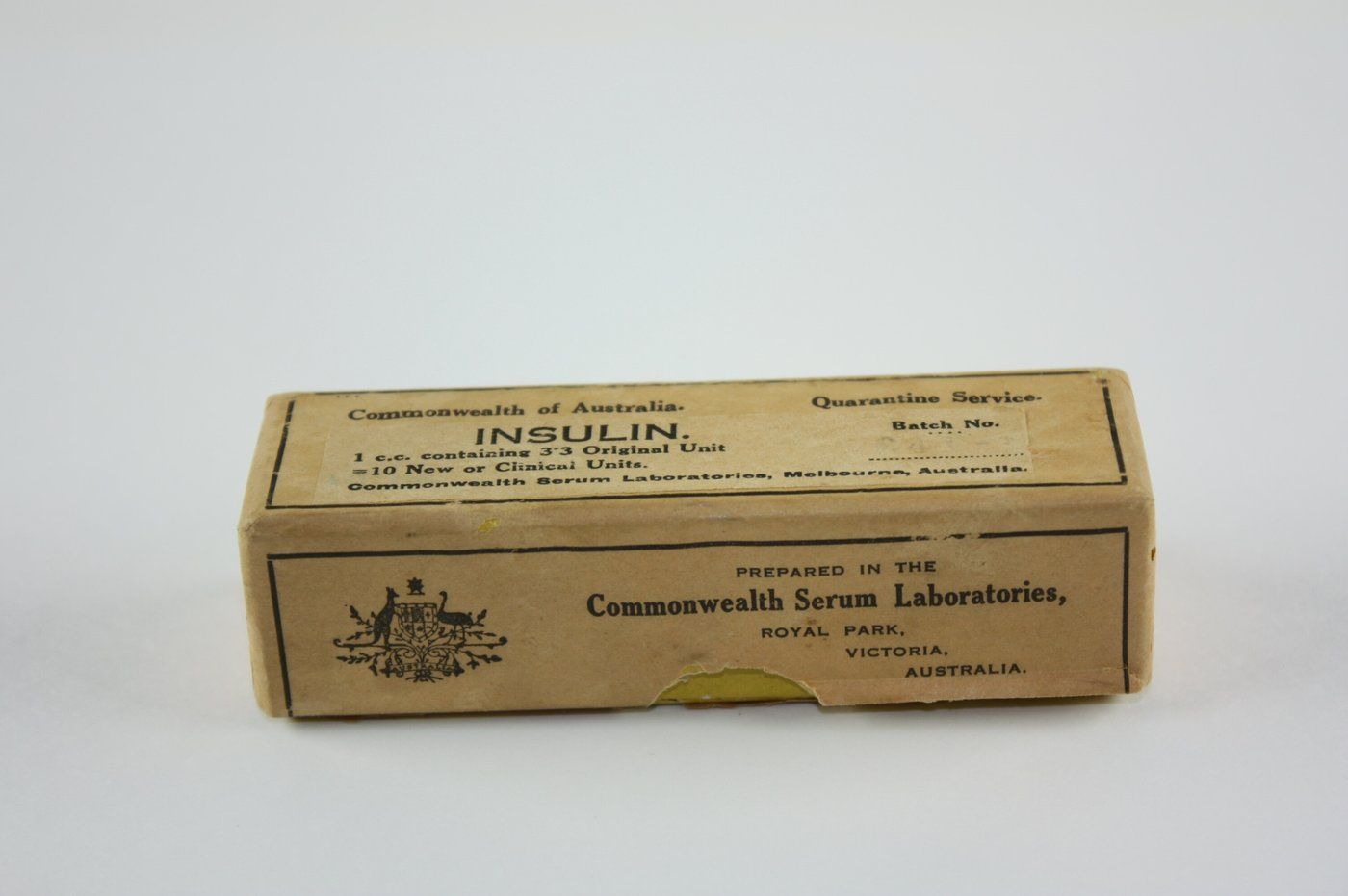

A group of researchers at the University of Toronto — Frederick Banting, Charles Best, James Collip and JJR Macleod — perfected the novel technique that extracted and then purified animal-sourced insulin, the pancreatic hormone that they proved regulated blood glucose levels. Banting and Macleod won the Nobel Prize for their discovery.

While the centenary celebrations of insulin’s discovery were muted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the moment allows for reflection on the current state of diabetes.

The term ‘diabetes’ was first used around 250BC and applied to a constellation of symptoms, including sweet urine and unexplained weight loss, that caused lethargy, coma and death.

The core pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus is elevated blood glucose levels, typically due to either absolute insulin deficiency (seen as type 1 diabetes mellitus) or overweight and obesity causing resistance to the actions of the body’s intrinsic insulin (seen as type 2 diabetes mellitus).

At the time of insulin’s discovery, diabetes mellitus was mostly seen in the industrialized North. Cases were predominantly type 1 diabetes, which meant it was amenable to treatment by insulin therapy.

Over the past century, however, with the rising global obesity epidemic, the burden of diabetes has come to be dominated by type 2, and a truly international problem. In the past two decades, it has become one the world’s leading causes of morbidity and early mortality.

Since insulin’s discovery, greater understanding about diabetes’ pathophysiology has helped diabetes therapies move on from only insulin to oral agents that stimulate insulin release or reduced insulin resistance, so that diabetic comas, even if not fully preventable, have become survivable.

But as the incidence of type 2 diabetes skyrocketed, brought on by a global epidemic of overweight and obesity, it became increasingly evident that these therapies focusing on reduced blood glucose levels did not directly reduce cardiac and renal complications linked to diabetes. As a result, they had a blunted impact.

Since the 2000s, the number and mechanisms of diabetes therapeutics has evolved from just targeting blood glucose levels to more novel agents, such as those that look at diabetes’ sine qua non of sweet urine, or gut-focused agents that target appetite and satiety.

For the former, the renally acting glucose-sodium transport agents, clinicians were for the first time presented with convincing evidence of a diabetes-related therapy that actually reduced cardiac and renal hospitalizations and deaths.

The the latter gut-focused incretin agents, working on neuroendocrine hormones found in the gut and brain, have proved so powerful in their impact on weight loss that for the first time there are medications that can potentially reverse type 2 diabetes.

However, these newer agents are costly and difficult to manufacture and distribute, which affects their availability and accessibility, especially for lower-income people and countries. On top of that, wealthy countries now hoard incretin agents for predominantly aesthetic or cosmetic reasons, rather than their capability as powerful treatments for diabetes.

More positively, potentially effective and low-cost public health strategies – mandated food labelling; promotion of healthy diet, activities and lifestyle; and childhood and early education obesity prevention strategies – have become more widely adopted.

In urban environments, prioritizing public transport, pedestrians and cyclists over private vehicles and implementing public taxation policies for energy-dense beverages and foods have all had success in various jurisdictions in moderating the rise of overweight and obesity and type 2 diabetes, including in Mexico, South Africa, the US and the UK.

Indeed what is striking is the relative success of the Global South in implementing many of these interventions, compared with Australia, which only launched its national comprehensive strategy in 2022.

Since Leonard Thompson and the team of Toronto researchers made history in 1922, the burden of diabetes mellitus has increased markedly and spread to where it is among the leading global health concerns.

Yet alongside this challenge has been a growing public awareness of the drivers of this increased prevalence, the development of medical therapies that for the first time reduce the mortality of diabetes’ associated complications and can potentially put type 2 diabetes into remission, and an increasingly sophisticated public health response that looks at a multi-sector and multi-system approach to reduce the underlying cause of type 2 diabetes.

Still, significant obstacles remain in the cost and accessibility of the most advanced therapies and in the willingness of governments to implement an effective public health response.

(The author is a Conjoint Senior Lecturer with UNSW Sydney, Senior Fellow with the Liverpool Diabetes Collaboration, Ingham Institute of Applied Medical Research and senior clinician affiliated with Liverpool and Royal Prince Alfred Hospitals, New South Wales, Australia. This article was originally published under Creative Commons by 360info)