Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP are medications that are highly effective at reducing the risk of HIV transmission, but they don't work for everyone.

HIV has been around for more than 40 years, yet it remains a major public health problem.

While HIV is commonly thought of as an infection that predominantly affects men who have sex with men, 53 percent of people living with HIV in 2022 were women and girls.

And of the 1.3 million new HIV infections that year, 46 percent were among adolescent girls and women, the majority living in sub-Saharan Africa.

Driving down new HIV infections is a key part of achieving a 90 percent reduction in HIV infections by 2030, as called for in the Sustainable Development Goals.

But it will require access to a variety of prevention methods to ensure all those at risk of contracting HIV can choose methods that best suit their circumstances.

Eliminating HIV transmission currently relies on using antiretroviral drugs in two different ways.

The first is 'treatment as prevention', whereby the viral load in someone living with HIV is suppressed to undetectable levels.

This strategy underpins UNAIDS 90-90-90 campaign to test 90 percent of individuals, ensure that 90 percent of these individuals are on treatment, and that 90 percent of these individuals are fully suppressed to decrease transmission of HIV.

A study published earlier this year in The Lancet confirmed that if someone's viral load is less than 1,000 copies of the HIV virus per milliliter of bodily fluids, the risk of HIV transmission through sex is virtually zero. This finding supports the Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U) global campaign.

The second strategy is HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, in which antiretroviral drugs are used to protect individuals at high risk of acquiring HIV through sex from their partners.

First generation HIV PrEP was approved in 2012. An oral pill called Truvada combines two antiretroviral drugs, tenofovir disoproxil and emtricitabine, which target reverse transcriptase, a key HIV protein the virus needs to reproduce.

Oral PrEP works, as long as those using it remember to take it.

Men can miss some doses of PrEP and still be protected from HIV, but oral PrEP is less forgiving if a woman misses taking her daily pill.

Daily pills are needed to maintain protective drug levels in the vagina, which is the main route of HIV acquisition in women. In contrast, higher drug levels are reached in the rectum, which is the main route of HIV entry in men who have sex with men.

Context is important is understanding why women don't just take their daily oral PrEP.

Oral PrEP use in adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa is associated with stigma due to lack of pill storage options, which makes discrete use of the medication difficult, and side effects.

In addition, daily oral regimens are challenging for adolescent girls and young women to stick to. While adherence might be high at the start of taking oral PrEP, it decreases over time.

Having the ability to choose from and access a variety of PrEP methods allows women to choose what suits their different contexts and what is suitable at different points of their reproductive lifespans.

Women may prefer PrEP that is delivered in a different way — for example, via injection or implant, or vaginally — as well as medication that is longer-acting and requires less frequent dosing — for example, once every two months or less often, as opposed to daily.

Choice and diversity of options resulting in an increase in adherence and uptake is well established for contraceptives to prevent unplanned pregnancies. The same options could be provided for women to protect themselves against acquiring HIV.

Second-generation PrEP options include the long-acting injectable cabotegravir. Cabotegravir belongs to the class of HIV drugs called integrase inhibitors. It is delivered into the body by intramuscular injections once every eight weeks for protection against HIV.

A phase three randomized clinical trial performed in seven countries in sub-Saharan Africa showed that the efficacy of injectable cabotegravir was greater when compared to daily oral Truvada for preventing HIV in uninfected cisgender women. Only four women became infected in the cabotegravir group, compared with 36 in the Truvada group.

While oral and injectable PrEP medications are effective, not all women want to take systemic forms of PrEP, because of fear of side effects. These women may prefer a topical form of PrEP, for example direct delivery of the antiretroviral drug into the vagina.

Vaginal delivery of drugs is an untapped frontier for drug discovery.

For topical PrEP, this has the advantage of delivering high antiretroviral drug levels locally in the vagina, with minimal drug levels in a woman's system, minimal side effects and a reduced chance of the virus becoming resistant to the drug.

Vaginal delivery can come in a variety of forms, including gels, tablets, films and intravaginal rings.

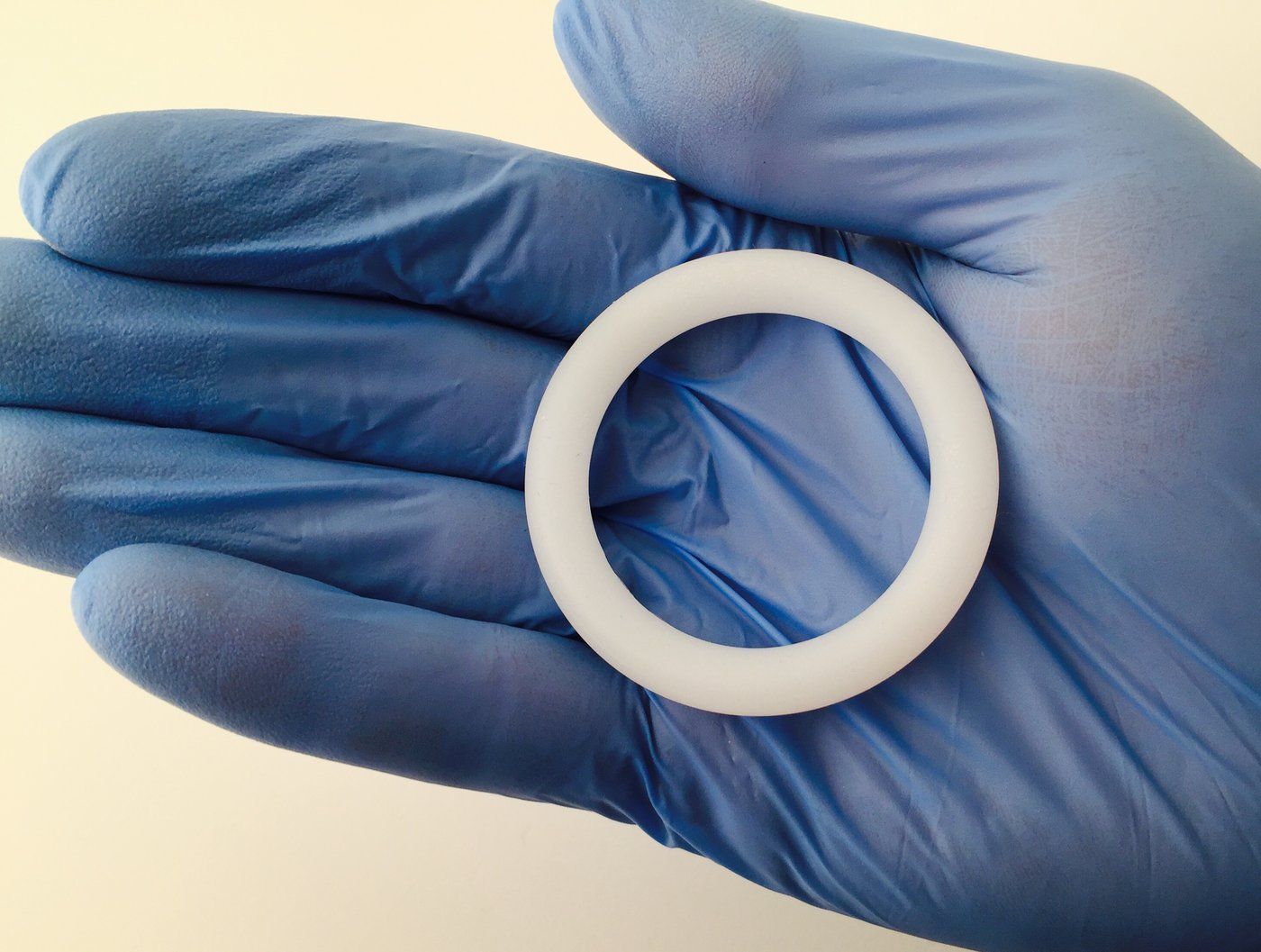

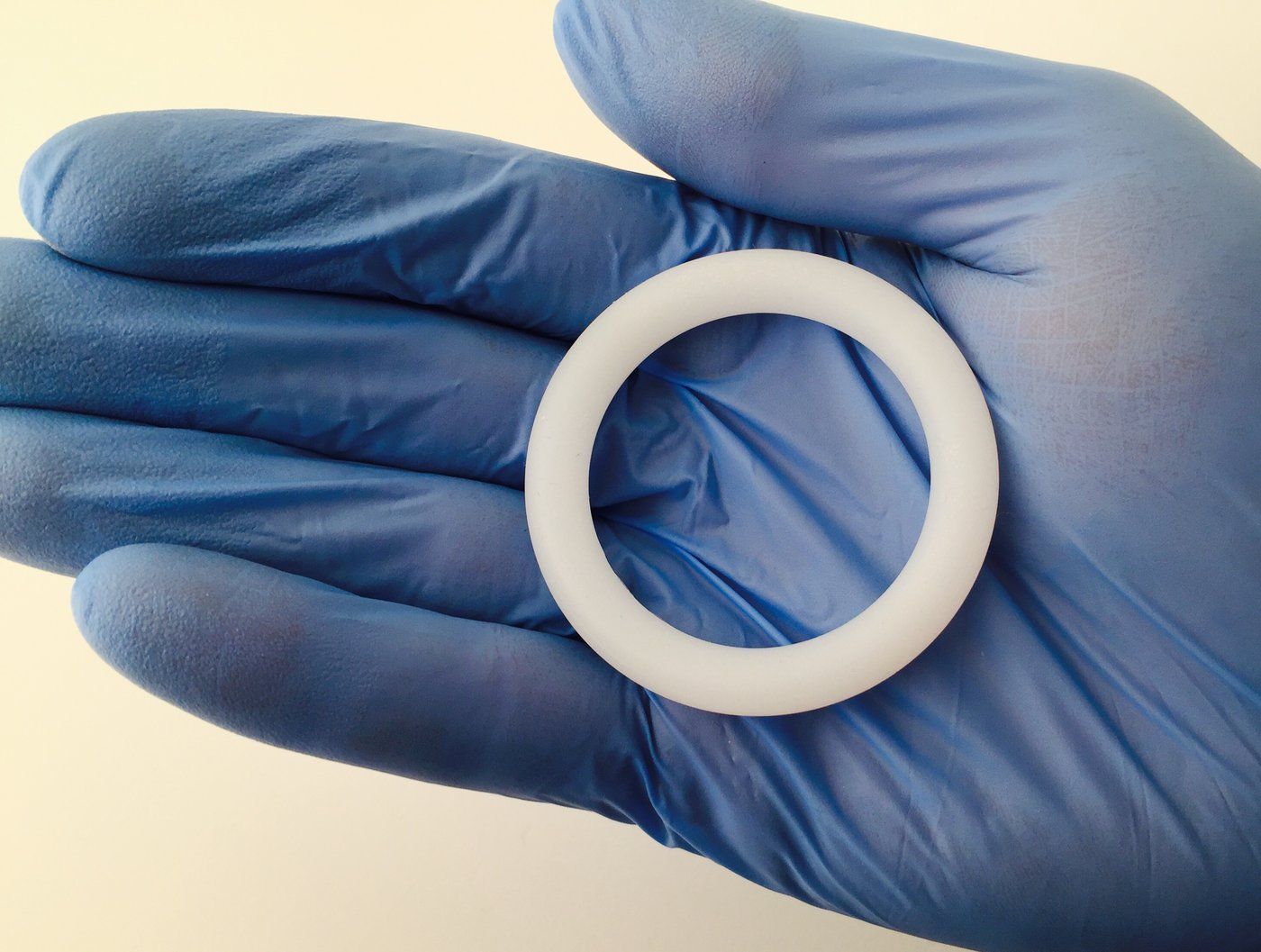

However, the only form of topical PrEP that has so far shown efficacy in preventing HIV infection in phase three clinical studies is the dapivirine ring.

The dapivirine ring is the only PrEP strategy specifically designed for women. It is an intravaginal ring made of flexible silicone loaded with 25mg of the antiretroviral drug, dapivirine, which is gradually released into the vagina over a four-week period.

Phase three studies showed the dapivirine ring could reduce HIV acquisition by 30 percent compared to a placebo ring, with efficacy being lower in women younger than 21 years of age due to low adherence.

However, follow-up studies with the dapivirine ring showed that it could provide about 50 percent or more protection if used consistently.

The ring received WHO prequalification in 2020 and has regulatory approvals in a limited number of countries, including Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

There are also devices in the development stage that go one step further, called multipurpose prevention technologies.

These include intravaginal rings designed to not only prevent HIV but also prevent unplanned pregnancy and even treat bacterial vaginosis.

Bacterial vaginosis commonly occurs when the bacteria living in a woman's vagina are out of balance.

The condition results in vaginal inflammation and increases the risk of a woman acquiring HIV and other STIs, as well as increasing the risk of other adverse sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

In contrast, women who have an optimal vaginal microbiome, dominated by beneficial bacteria, are protected against HIV.

A product delivering molecules to the vagina that can target or prevent bacterial vaginosis as well as prevent HIV may also increase the efficacy of topical PrEP.

One device addressing multiple targets has the advantage of potentially addressing stigma associated with an agent specifically being used to prevent HIV, in addition to improving compliance and ultimately effectiveness.

Women having choice and access to diverse biomedical HIV prevention strategies and input into the design of these interventions will be important for achieving the goal of eliminating HIV transmission by 2030.

(The author is a Senior Principal Research Fellow at the Burnet Institute and Adjunct Professor at Monash University. Her research focuses on antivirals for HIV treatment and prevention, with a particular focus on HIV prevention in women and understanding the role of the vaginal microbiome in modulating HIV acquisition. This article was originally published under Creative Commons by 360info)