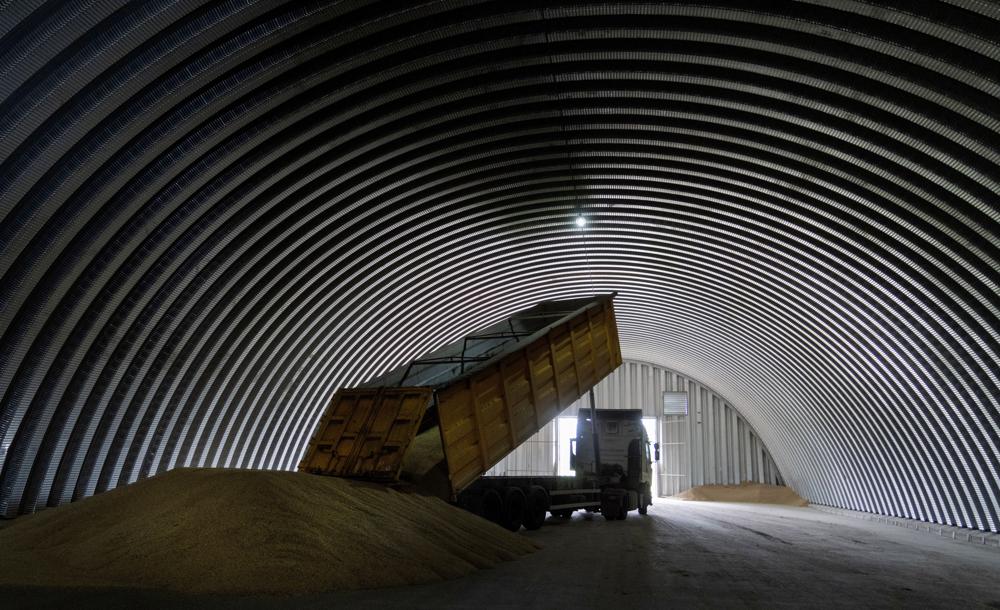

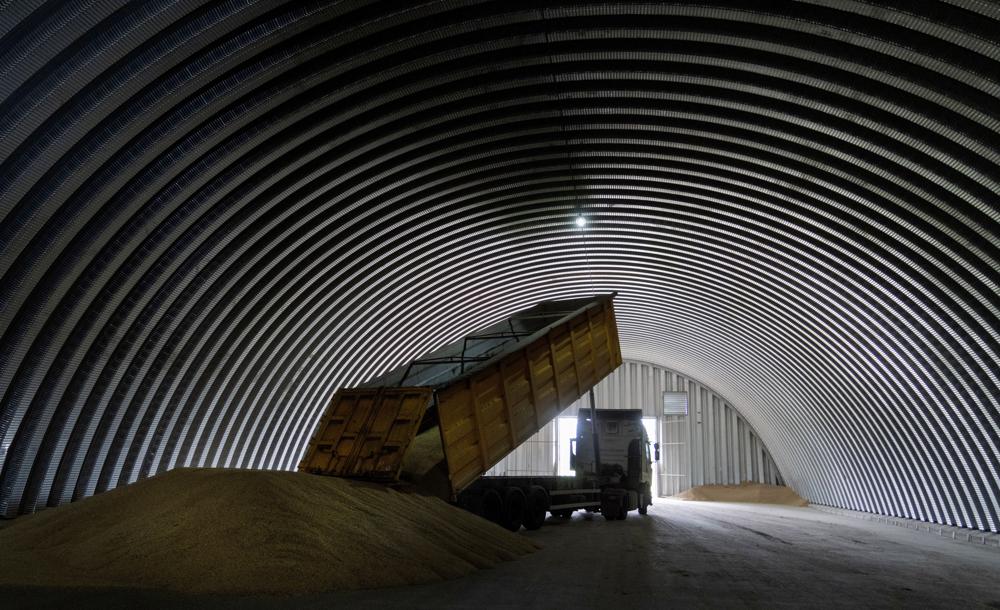

A wartime agreement that unblocked grain shipments from Ukraine and helped temper rising global food prices will be extended by four months, the United Nations and other parties to the deal said Thursday, preventing a price shock to some of the world’s most vulnerable countries where many are struggling with hunger.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy called the 120-day extension a “key decision in the global fight against the food crisis.” Struck during Russia’s war in Ukraine, the initiative established a safe shipping corridor in the Black Sea and inspection procedures to address concerns that cargo vessels might carry weapons or launch attacks.

The deal that Ukraine and Russia signed in separate agreements with the U.N. and Turkey on July 22 was due to expire Saturday. Russia confirmed the extension but said it expected progress on removing obstacles to the export of Russian food and fertilizers.

Ukraine and Russia are key global suppliers of wheat, barley, sunflower oil and other food to countries in Africa, the Middle East and parts of Asia where millions of impoverished people lack enough to eat. Russia was also the world’s top exporter of fertilizer before the war. A loss of those supplies following Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine had pushed up global food prices and fueled concerns of a hunger crisis in poorer countries.

While the extension prevents a price shock in developing nations that spend far more on food and energy than richer countries, threats persist from droughts in places like Somalia and the weakening of currencies around the world, which makes buying imported grain more expensive.

“I was deeply moved to know that in Istanbul, Turkey, Ukraine, Russia and the U.N. had come to an agreement for the rollover of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, allowing for the free exports of Ukrainian grains,” U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said.

The Turkish Defense Ministry said the decision to extend the deal came after two days of talks in Istanbul between delegations from Turkey, Russia, Ukraine and the U.N. that were held in a “positive and constructive” atmosphere.

Russia had voiced dissatisfaction with the deal facilitating exports of Russian grain and fertilizer, hinting that it might not approve an extension and even briefly suspending its part of the deal late last month. It cited risks to its ships following what it alleged was a Ukrainian drone attack on Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.

Although Western sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine did not target food exports, many shipping and insurance companies were reluctant to deal with Moscow, either refusing to do so or greatly increasing the price.

Guterres said the U.N. was “fully committed” to removing hurdles to shipping food and fertilizer from Russia.

The United Nations has been working to overcome issues related to insurance, access to ports, financial transactions and shipping for Russian vessels, according to a U.N. official who was not authorize to speak publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity. The official said the insurance issue has mainly been resolved in recent days.

Russia has offered to donate 260,000 metric tons of fertilizer stored in European ports to farmers in the developing world who have been priced out of the fertilizer market because of shortages, and the official said the first ship is slated to leave the Netherlands on Monday for Mozambique, where the fertilizer will go by land to Malawi. Further shipments are expected from Belgium and Estonia, the official said.

The Russian Foreign Ministry said Moscow had allowed the extension to take effect “without any changes in terms and scope.” It said Russia noted the “intensification” of U.N. efforts to hasten Russian exports.

“All these issues must be resolved within 120 days for which the ‘package deal’ is extended,” the ministry said.

During talks on the extension, the sides discussed possible additional measures to “deliver more grain to those in real need,” the ministry added, apparently to address Russian complaints that most of the grain has ended up in richer nations.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan suggested Thursday that wheat from Russia could be turned into flour in Turkey and shipped to African nations in need.

U.N. humanitarian chief Martin Griffiths said last month that 23% of the exports from Ukraine under the grain deal have gone to lower- or lower-middle-income countries and 49% of all wheat shipments have gone to such nations.

Markets were pleasantly surprised by the extension, said Ian Mitchell, co-director of the Europe program at the Center for Global Development who specializes in agriculture and food security. Following the announcement, wheat futures prices dropped 2.6% in Chicago.

“Ukraine and Russia are such important grain exporters that the rest of the market can’t fully substitute for the complete absence of Ukrainian grain,” he said. “So that deal is going to matter to food prices significantly, even if the volumes are not what they were before the invasion.”

He said, however, that uncertainty is “unhelpful in this deal.” Toward the end of the four-month extension, markets will “price in the risk that it wasn’t extended, and prices will rise a little bit again.”

Arnaud Petit, executive director of the International Grains Council, said the Black Sea region produces some of the world’s cheapest wheat and securing those supplies prevents a price shock to developing nations.

There have been good harvests in the region, contributing to an expected 10 million more tons of wheat worldwide compared with last year, he said. The extension means that Ukrainian farmers can plan to plant.

Petit called the extension a building block in “an unstable region where things can change on a daily basis.”

However, when it comes to food prices, trade movement isn’t as important as currencies around the world weakening against a strong U.S. dollar, which commodities like wheat and other grain are priced in, Petit said.

The council calculated that for Ghana, which mainly imports its wheat from Canada, the price of wheat in dollars from Canada has been largely stable for two years. But changing into local currency translated to a 70% price hike.

Global food prices declined about 15% from their March peak after the grain initiative was adopted in July.

“With the delivery of more than 11 million tons of grains and foodstuffs to those in need via approximately 500 ships over the past four months, the significance and benefits of this agreement for the food supply and security of the world have become evident,” Turkey’s Erdogan said.