The huge public outcry to fix the system and the demand for justice following the rape and murder of 13-year-old Nirmala Panta gave me, if nothing else, a little hope for the upliftment of women’s situation in Nepal. That reminded me of Jyoti Singh’s gang rape and murder which shook India to its core and made the people come together as a nation to look at the existing traditions and political system that allowed such atrocity to take place. On the one hand, it is inspiring to see how much attention people can draw to important issues if they genuinely feel a need for change. But on the other hand, it astonishes me that South Asian countries like Nepal and India need horrific crimes like a girl getting brutally murdered after having a rod inserted in her vagina or a 13-year-old raped and thrown in a sugarcane field for people to finally be enraged and take action. Can we not get angry when a girl becomes the subject of a perverted male gaze in a public vehicle? Or is the intensity of the situation not urgent enough and we have to wait for the girl to be brutally raped?

According to the data maintained by Nepal police, in the fiscal year 2073/74 ending in July, 2017, 1,117 cases of rape and 527 attempts to rape were reported. Yet, cases of harassment and violence against women only feature in tiny five-line columns in newspapers or 30-second segments in televisions. Is that all the attention merited by such serious issues? We have let such heinous crimes repeat over and over again so many times that a couple of harassment and rape cases in a newspaper barely draw a glance from the reader. It sounds horrific to say, but we have normalized rape and violence against women in our society.

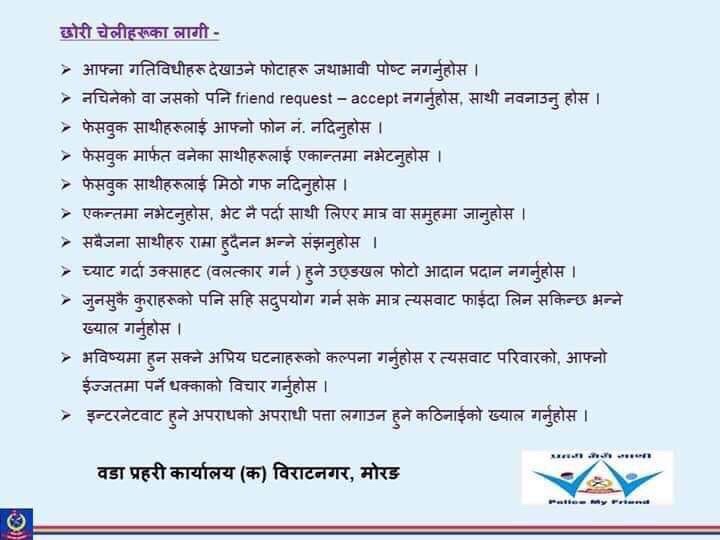

Few weeks ago I came across a notice by Nepal Police, Biratnagar with a title “For chhori/ cheliharu (daughters/sisters) including 10 bullet points mentioning what they should and should not be doing, especially on the internet. Two of the mentioned points were, “while texting online, do not exchange excitable pictures that would encourage rape” and “think about the consequences the unsuitable accidents might bring to the reputation of your family.”

Let’s start with the term chhori/cheliharu which is grossly overused in every context in Nepal. The patronizing term refers to women not as independent beings by themselves, but in relation to somebody else, implicitly men. It implies that women cannot exist without a male point of reference and need men to validate their existence. Do we ever refer to men in Nepal as chhora/chelaharu (sons/brothers)? If not, why are women always referred to in terms of some relationship to men be it chhori/cheli or didi/bahini? Even now, our society refuses to accept that women are capable of standing on their own feet and leading a happy and successful life without any support from men.

Furthermore, when Dr Govinda KC was staging his 15th fast-unto-death demanding reforms in the medical sector, our former minister for law, justice and parliamentary affairs, Sher Bahadur Tamang, also pulled out the chhori/cheli trump card while casually talking about chhori/cheliharu in Bangladesh “losing their honors” by sleeping with teachers to earn their MBBS certificate. He had done no research and provided no facts to back this claim, and was possibly working just to promote his own agenda regarding medical schools. So not only is violence against women being brushed aside in a patronizing manner, it is also being used as a political tool.

Going back to the notice, we have a classic example of victim-shaming. An official government document instructing women to be conscious of their own bodies and explicitly stating that a woman’s own action triggers rape. The notice completely ignores a woman’s right to befriend, talk to, or exchange pictures with whoever she chooses and instead follows the age-old narrative that what matters the most when you are a Nepali woman, is to live and die protecting this fragile and sacred thing called “family’s honor”. Why do we forget a Nepali woman has every right to share whatever personal, political or sexual content she wants to? I don’t see men being reprimanded for the exact same actions. Equally saddening is the fact that nobody is pointing out the absurdity of the notice. What we need is a notice that warns the perpetrators to change the way they behave, not the victims. A notice that would help create a secure environment for a woman to freely express herself. A notice which stresses that sweet-talking or exchanging pictures, even including nudes, is not an invitation to rape. A notice that encourages a safe culture of consent.

The age of consent in Nepal is 18 years and getting involved in any sexual activity with someone under that age, even if they are willing, is considered rape. Consent means that not only must men stop when a woman says NO, but men must not proceed unless a woman says YES. This does not change even if two people are married or in a relationship. Do we teach this in schools or families in Nepal? Each month hundreds of marital rapes do not get reported as the body of a married Nepali woman supposedly becomes her husband’s property and women are conditioned in such a way that question of consent does not even come up.

Sex scenes in movies do not feature people asking for consent, leading people to assume the same in their daily life, especially in the South Asian communities. Amitabh Bachchan starrer Bollywood film Pink is a recent exception and is trying to draw India’s attention to the culture of consent. How effective it has been in doing that has yet to be seen but, at the very least, it is a step in the right direction. Hopefully Nepali entertainment industry will soon follow suit. It is also important to notice less extreme examples like sexist songs promoting slut-shaming which turn out to be the biggest hits. Admittedly, such examples do exist in Bollywood and Hollywood but the difference is that they have been receiving their share of criticism. But here, how many of us even notice that?

I have seen the most intellectual women go quietly to the kitchen while men have conversations in the living room. I have gone to a restaurant and seen the menu being passed to a guy, deeming him to be the decision-maker. I have seen countless cases of mansplaining, men explaining things to women who are expected to just nod their heads for hours. I have heard a group of boys burst out into laughter on rape jokes, not realizing or simply not caring about the sensitivity of the subject. These are the subtle ways in which we take power away from women and accept a male-dominated order of society. Every time this happens, and nobody speaks against it, we take the first steps toward normalization of rape culture.

Stricter laws against rape are definitely needed and, with the enormous public pressure, inevitably are forthcoming. But that will just be the top of a pyramid whose base we are yet to build. How can we let men get away with catcalling and slut-shaming and then be certain they will not take the next step and attempt a rape? Bestowing all the power on men, we have promoted this culture of rape and now we cannot just punish one culprit and expect to stop all rapes. We all are culprits to have let the situation worsen to this extent and we all need to make amends. Working from the ground level to uplift the status of women in Nepal and making sure no action, no matter how small, that undermines women’s standing in the society as equal to that of men goes unchecked, should be the initial steps toward that atonement.