As I sit by my ailing father, I have an impression of him representing an era of slowly vanishing Limbu culture and tradition of Mundhum-based rites and rituals.

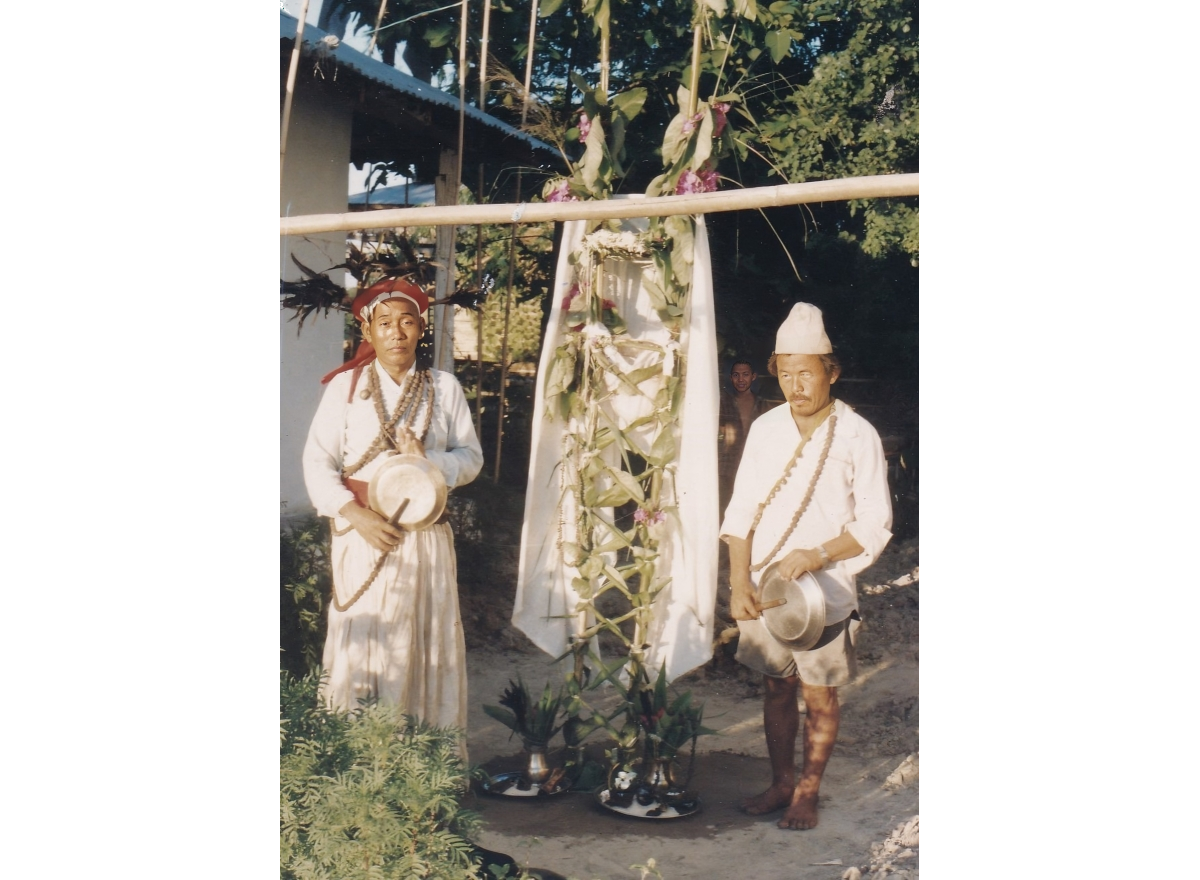

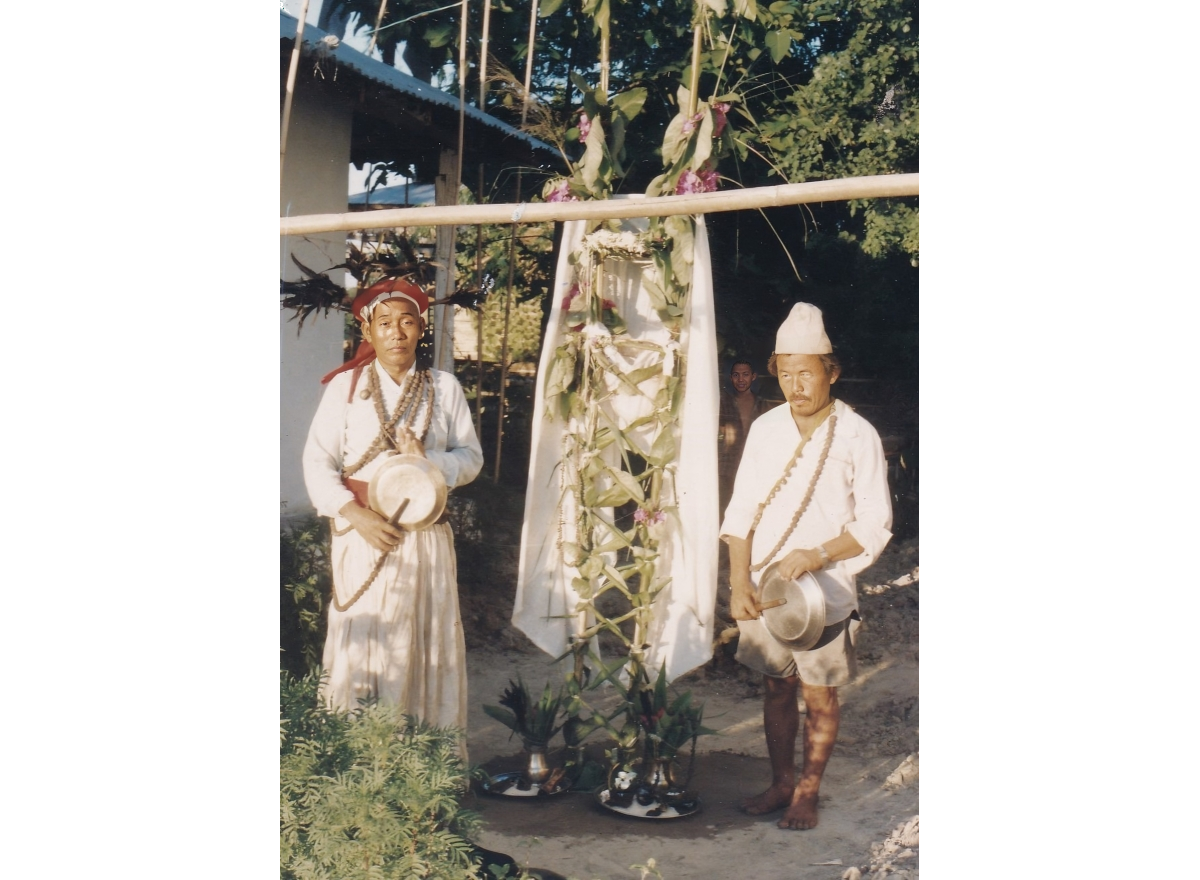

I still vividly remember how vehemently he performed the ritual of Tongsing Takma as a Yeba (Limbu shaman assigned for carrying out various rituals) some decades ago. In the night of the ritual performance, he would wear long white robe tightened at the waist, a headdress decorated with the feathers of different birds and garlands made from the beads of rudraksha. For the whole night, he would recite Mundhum and dance around the bamboo pole known as Yagesing fixed for the ritual in the middle of the courtyard. As a boy, I could hardly grasp the eloquence of his Mundhum recitation and message of those rich oral scriptures. For me, the event was simply an occasion of celebration and fun where I enjoyed ludicrously following and copying his dancing steps and panicked and thrilled being chased by him in the middle of the ritual performance along with others.

Back then, Limbu community operated differently. They observed their own distinct life rituals including Tongsing Takma. The night of Tongsing Takma was not only an event for ritual performance but it was also a social gathering for the entire villagers. Some of them would come to join hands for the different responsibilities including feeding Tongba (millet beer served in a wooden barrel shaped vessel) and other local liquor to the visitors while others would come to know their fortune from the words of the Yeba, my father. Others joined the Yeba and his Yagapsiba (assistant of the Yeba) in the ritual dance carrying and beating brass plates. For majority of villagers, it was a pure form of an entertainment free of invitation. Everyone was welcomed in the night of the Tongsing Takma ritual.

The decade of 1990 ushered prodigious changes in Nepali politics as well as in sociocultural realms. The Janaandolan of 1990 saw an end of absolute monarchy replaced by constitutional monarchy and multiparty system ending three decades of party-less Panchayat system imposed by King Mahendra in 1960. The same decade also worked as a harbinger for the country embracing neoliberal ideals as the panacea for socio-economical transformation. Nobody thought of far-reaching implications of the incipient systems to the local language, culture, knowledge system and social structures of the indigenous people.

Same applied to the Limbu people, chiefly inhabiting the eastern part of Nepal. In addition to joining British and Indian armies as Lahure, many Limbu youths followed the footsteps of other Nepali migrant workers making destinations mainly to Malaysia and the Gulf Cooperative Council countries including Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Kuwait among others. As foreign employment became a major source of income for many a Nepali households in the last three decades, it further provided an impetus for people to migrate from the hills and mountains to the plain regions of Tarai and from rural villages to city and towns, thus bringing unprecedented changes in rubrics of society and culture.

Such migration trends not only resulted in the shortage of working age people in the villages but also brought changes in demographic and economic structures of towns and countryside leaving the family members of migrant workers increasingly dependent on the remittance they send from abroad. Accordingly, people fell under the charm of consumerism ultimately debilitating the bonds of social relationship and cultural convictions of the indigenous people. As everybody seemed lost in the reservoirs of containment by hailing the contribution of Nepali migrant workers to the economic development of Nepal, nobody seemed cognizant of the disconcerting side of the coin, the breakdown in the family structures and cultural mosaics. The void was not only created in the local labor markets, but also in the urgency of indigenous cultural behaviors and ritual practices.

In the past, my father used to remain busy throughout the year serving the village households as Yeba, performing different rituals of Limbu community like Sappok Chomen (ritual for womb worshipping prior to birth), Mangenna (ritual for good health, peace and progress), Mekkhim (ritual for marriage ceremony) etc. Due to his engagement in such activities of the community, I sometimes used to hear him complaining about not having time for his own household chores as a farmer. But he readily served the community on such occasions. I still remember how my father used to take pride in his narratives of being kidnapped by a supernatural wild shaman in his childhood who taught him the sacred knowledge of Mundhum and turned himself a self learnt Yeba, as one of the chosen persons by the God to save Limbu community from the various misfortunes and sickness. Gradually, my father and fellow Limbu shamans commonly called as Phedangma, Samba, Yeba and Yuma not only found their roles being drastically limited within the community, but they also failed to pass their knowledge to the next generation.

Hermeneutics of Tongsing Mundhum

According to Mundhum scholar Bairagi Kaila, Tongsing Mundhum is an extreme expression of social, ethical and religious beliefs of Limbu people. He writes in Tongsing Takma Mundhum: Aakhyan Ra Anusthan (Tongsing Takma Mundhum: Narratives and Rituals) that Tongsing Mundhum is a quintessential collection of oral literature and ethnic narratives that have been transferred orally from the time immemorial to the Limbu people. This Mundhum is recited and narrated along with music of brass plates and drums by Limbu shamans known as Samba, Yeba, and Yema during the performances of Tongsing Takma ritual. It is believed that Tongsing Mundhum was originated long before the art of writing was introduced.

According to scholar Chaintanya Subba, various myths, legends, narratives and oracles have been incorporated in Tongsing Mundhum which guide the social, ethical and religious concepts and shape the attitude and behavior of the Limbus. It consists of the various myths related to the origin of universe, human beings, plants and animals, and birth of the concepts of incest, jealousy, curse etc. in human society and the remedies for different problems in the society.

Limbus believe that there have been substantial influences of the Tongsing Mundhum in the customs, ideologies, moral values and life rituals of the Limbu community. It has a distinct pragmatic and instructional value with regards to the construction and continuation of various social practices and belief system in the Limbu community. It has played a crucial role in imparting the message of social solidarity and cooperation. However, there remains an effectual task for us to explore the social dimensions of Tongsing Takma ritual impacting the social life and practices of Limbus in the past.

Modernization has resulted into an irreversible loss of Limbu cultural heritages and ritual practices. A handful of enthusiasts of Limbu community are in disagreement themselves on which terminology best describes Limbu religion and cultural landscapes. Each group claims its own validity over the other but ironically overlooks the urgency of passing the knowledge to the coming generation. They don’t realize that culture and rituals live in society, not in institutions and books. If such cultural values can not be transferred to the coming generation, they would be the matter of history, to be searched in anthologies and museums. We certainly do not want that. So, rather than castigating others, we need to explore the nostrums to address the present challenges.

As the majority of young generation are detached from such ritual practices, an irreparable cultural void is being created every day. Incipient danger is that present generation could be the last generation of Limbu community practicing and living with the distinct cultural practices and Mundhum-based life rituals. As remaining Phedangma, Samba, Yeba and Yuma have failed to transfer their knowledge to the young generation, it would be very hard to find their disciples practicing these rituals through the oral recitation of Mundhum after one or two decades. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t want this to happen either. But I have not seen any other possibility too until we carry the torch of responsibility to stand as bulwarks to protect and preserve our distinctive cultural traits before they are pushed into oblivion by the varieties of intrusions.

Today, Tongsing Takma and other rituals have become rare events in Limbu community due to two main reasons: first, very few Limbu Phedangma, Samba, Yeba, and Yema are left in the community who can perform them in a proper way and second, young generation have no inclination to follow these rituals as they are gradually losing interest in the past ideals. This is not simply the fault of young generation living under the overwhelming fluctuations of information and technology. We must take responsibility for not infusing them cultural consciousness and not persuading them to adopt these value systems in everyday life.

Nowadays, a very few households are conducting Tongsing Takma and other rituals as a part of their daily lives mostly in remote villages. Some enthusiastic individuals and institutions are conducting this ritual in Kathmandu and other towns too. But such events largely become a simulacrum of the real Tongsing Takma, more as a frail attempt to recreate it and less as a distinct life rituals of the Limbu community. Such formalized occasions cannot persuade the heuristic value of these rituals to the coming generations.

The only positive sign in this area is there have been some works in the transcribing the oral scriptures of Mundhum recited by those Limbu shamans. In recent days, some Limbu scholars and writers have transcribed Mundhum in Limbu and Nepali language and have documented those ritual performances. In this direction, the colossus work of Mundhum expert Bairagi Kaila is always commendable. He has collected and transcribed most of the Mundhum with the help of Limbu Phedangma, Samba, Yeba, and Yema. I personally feel indebted to his huge contribution to the Limbu community by preserving Limbu Mundhum.

Years ago, in the night of the Tongsing Takma ritual, my father used to recite Mundhum and its myths in a rhythmic tone from his infallible memory followed by rhythmic beating of his brass plate and harmonious shamanic dancing steps. In the morning, he would perform the ritual of Silam Sakma (blocking the path of death) for the whole family concerned by reciting the Mundhum as:

A bright place due to the moon above us

A bright place due to the sun above us

In the place of life and age

Are life and age decreasing?

Are the bells of time and death ringing?

Now, without letting the death bell ring

I toss this incanted coin

To block the path of the death.

(Excerpts translated from the Tongsing Takma Mundhum: Aakhyan Ra Anusthan by Bairagi Kaila)

With these words, he would toss the coin in the name of each family member until the intended side of the coin overturned in the ground. The turning of the expected side of the coin is believed to have blocked the path of death, as a part of the ritual. I do not claim the efficacy of this ritual in the real time, but the psychological and mental asset of such rituals were certainly an important part of the community in past.

Once ardent practitioner of Mundhum based rituals, my father would spend hours discussing about Mundhum and its various myths deciphering their meaning and implications to us. He adored Mundhum as a treasure for Limbu community that teaches us to live in harmony with nature. He used to say all natural entities be it rivers, hills, caves, forests, or anything that we get from nature, have to be worshiped and preserved because they support human life in one way or the other. He was not being philosophical at that time, neither had he had any idea of the subject but he was simply passing his impression of Mundhum for our generation. Today, I feel that humankind have already deferred the deadline to respect the nature, by exploiting its resources to the fullest extent and wreaking an unprecedented havoc in its beauty. And obviously, we are getting paid by the effects of global warming and other disastrous natural phenomena for our irresponsible action towards nature threatening the existence of life in the blue planet.

Even though we listened to his stories enthusiastically, my father could figure out that his listeners were losing interests in them. Then his remarks would be same as always - time has changed…in our time………and so on. At this moment, I can sense the meaning of his words but the time has changed for me too. But what I fear most is I even may not have the same words to convey to my children by referring to the nostalgia of our time. The indispensable cultural values that we have inherited from our ancestors have been eroding with the passage of time. We are living in an age of cultural deviation and oblivion. Now, when I sit by my ailing father living in his early eighties, I sometimes envisage him as Truganini (1812 –1876) the last full blood Aboriginal Tasmanian, whose culture and identity were completely swept away by the wave of 19th century colonialism.