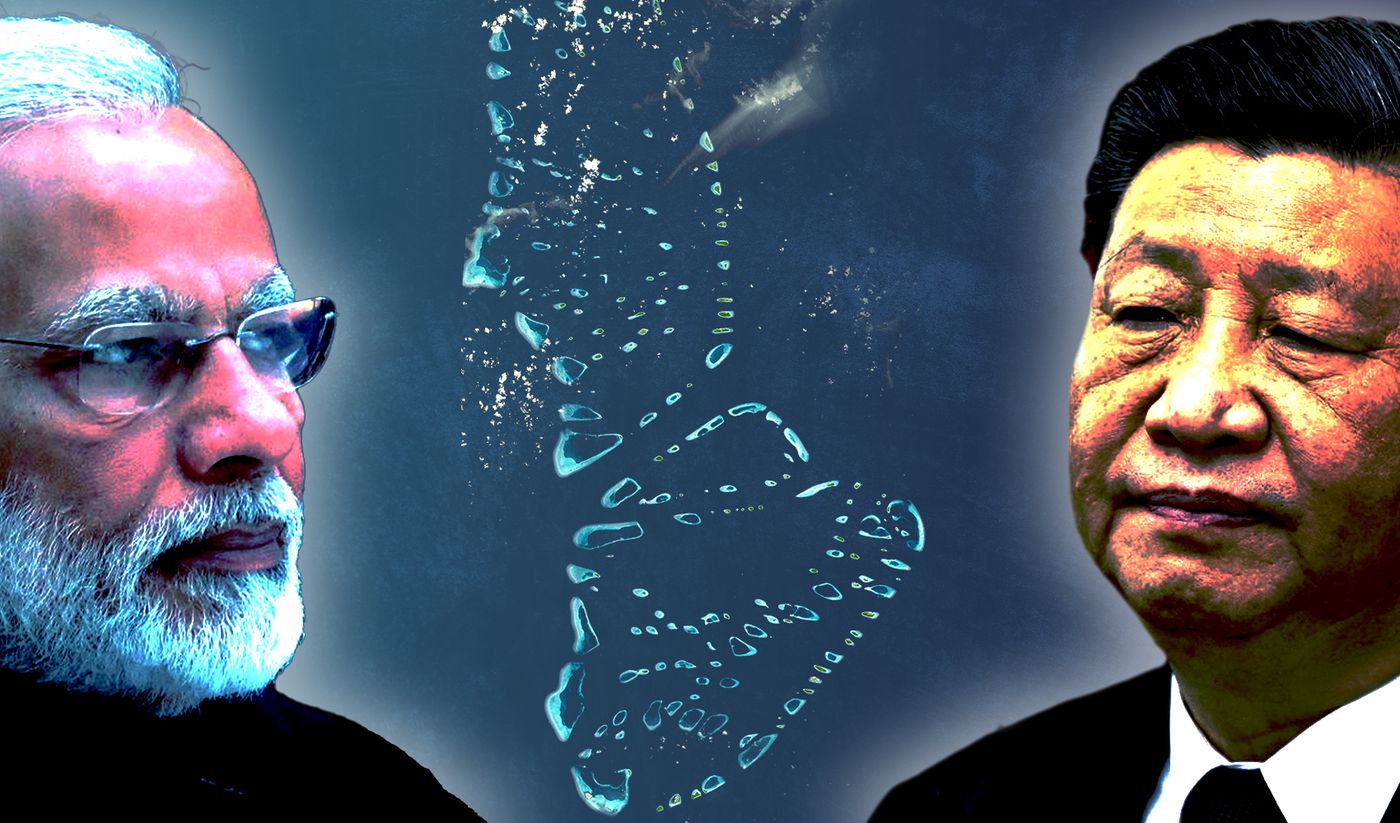

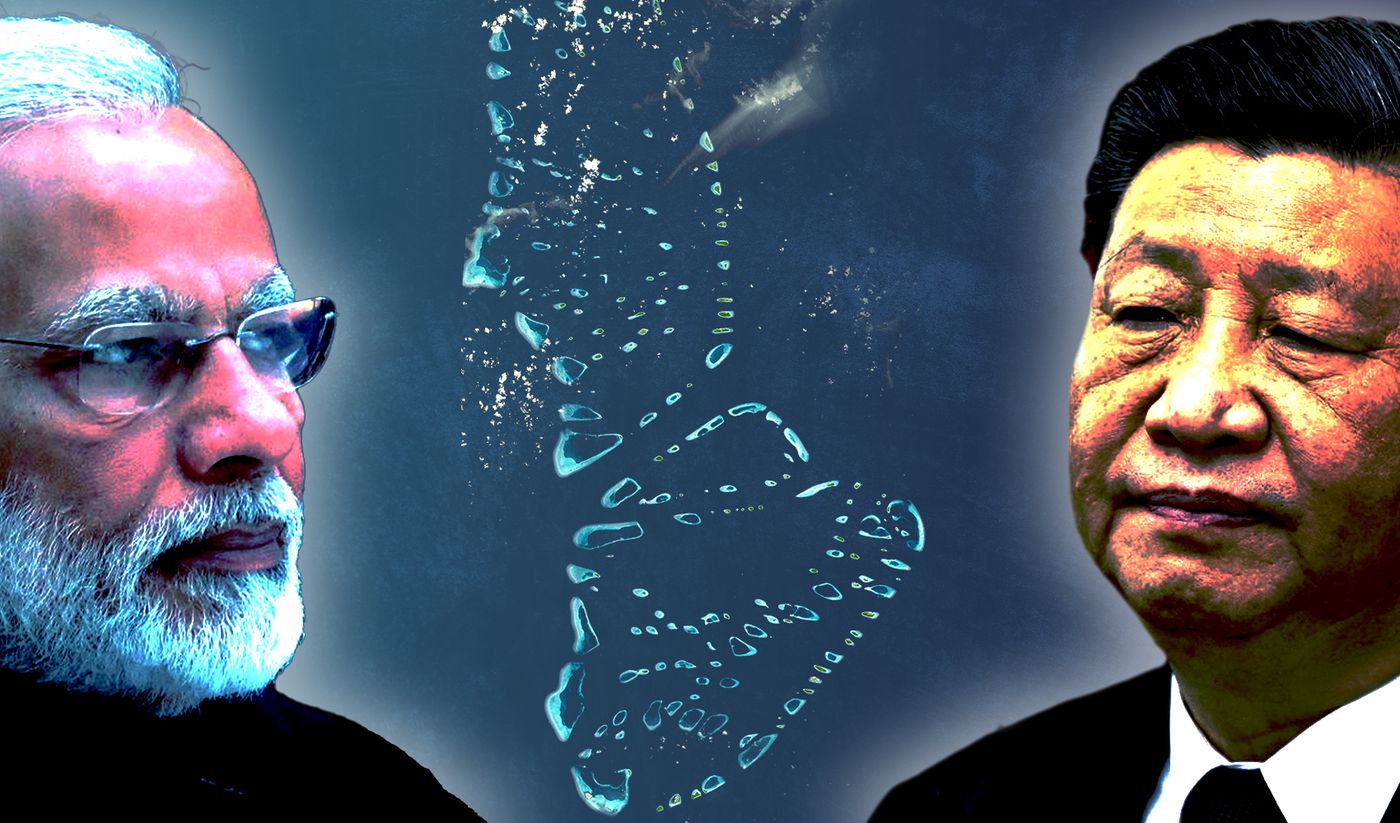

India has started pulling out its military personnel from the Maldives.

The move comes amid an intense diplomatic row, in response to Maldives president Mohammed Muizzu asking India to withdraw its symbolic military presence fully from the archipelago by May 10.

Muizzu declared on March 5: “There will be no Indian troops in the country come May 10. Not in uniform and not in civilian clothing. The Indian military will not be residing in this country in any form of clothing.”

This “military presence” consists of around 80 Indian troops, along with Indian Air force staff to operate Dornier 228 maritime patrol aircraft and two India-made Dhruv helicopters used for medical emergencies.

The Maldives has also decided to discontinue a pact under which India conducted hydrographic surveys in its territorial waters. It has decided to conduct them on its own.

While claiming that he is committed to protecting the sovereignty of the Maldives, Muizzu has also signed an agreement for “free military aid” with China. Going beyond normal investment and capital agreements, the defence agreement is expected to provide free non-lethal military equipment and training for the Maldivian security forces.

As China gains ground in the Maldives, the bilateral ties between New Delhi and Male have deteriorated fast.

On his return from China recently, Muizzu indirectly referred to India as a “bully” and said that the Indian Ocean “does not belong to one particular country”, and that the Maldives “is not in anyone’s backyard”.

Indian Foreign Minister S Jaishankar responded to the “bully” remark saying, “big bullies don’t provide USD$4.5 billion aid”.

He added: “Big bullies don't supply vaccines to other countries when COVID is on or make exceptions to their own rules to respond to food demands or fuel demands or fertilizer demands because some war in some other part of the world has complicated their lives.”

These acerbic exchanges point to the geostrategic competition in the Indian Ocean between India and China, in which India finds itself at the losing end because of the change of government in Male.

The Indian Ocean contains some of the most important chokepoints for maritime trade: the Strait of Hormuz, Bal-el-Mandeb, Straits of Malacca and the Mozambique Channel.

It is a critical route for energy supplies for China and India both as well as for their engagement with Africa, West Asia and the island nations and littoral states across the Indian Ocean.

China seeks to present itself as a credible and emerging security and economic partner for the Indian Ocean nations.

Many island and littoral nations in India’s backyard tend to play off China against Indian influence to gain foreign policy manoeuvrability.

Historically, India has had closer historical ties with the Maldives than China. However, which country has more influence in the Maldives at any time is determined by the domestic political equations in the strategically located archipelagic nation.

The pro-democracy forces in the Maldives normally tend to align with India. However, they are not always ascendant and there is a sizeable presence of pro-China political elements in the Maldives.

After the election of Muizzu and his Progressive Party of Maldives in September 2023, the geopolitical balance has swung in favor of China.

Previous president, Ibrahim Solih of the Maldivian Democratic Party, followed an “India first” policy, which was countered by the “India out” slogan by those who see Indian policy as heavy handed.

For the first four decades since its independence in 1965, the Maldives was firmly under Indian influence.

India supported strongman Maumoon Abdul Gayoom as president from 1978 to 2008. Indeed, India helped Gayoom suppress a coup engineered with the help of mercenaries by his opponents in 1978 by sending in its armed forces.

India has also been at hand for immediate as well as long-term assistance to the Maldives ranging from trade cooperation, natural disaster relief and supply of fresh water when the island nation’s desalination plants stopped functioning and COVID-19 vaccine assistance.In 2013, just when China was laying the groundwork for its Belt and Road Initiative , a pro-China president, Abdulla Yameen was elected to power.

He invited Chinese assistance for infrastructure projects in the Maldives – a new runway for the main international airport, a bridge between capital Male and the island of Hulhumale – and even signed a free trade agreement with China.

The Maldives had accumulated nearly USD$ 1.5 billion of Chinese debt by 2018, a large sum considering that its GDP is less than USD$ 9 billion.

In power, Yameen’s authoritarian tendencies’ were on full display.

Human Rights Watch accused him of “eroding fundamental human rights in the island country, including freedom of association, expression, peaceful assembly, and political participation” and of blocking the “opposition parties from contesting elections, the arrest of Supreme Court justices, and the crackdown on the media.”

Democracy was restored with the election of Solih in 2018. India was on top again. Solih pulled out of the FTA with China with India providing USD$1.4 billion for loan paybacks and other development assistance.

And now the tables have once again turned again in favour of China.

Besides the Maldives, the strategic competition between India and China in the Indian Ocean is also playing out in Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Seychelles and Madagascar.

Deepening US-China rivalry – especially the Chinese forays into the western reaches of the Indo-Pacific and opening up of a military base at Djibouti – has pushed Washington to recognize the geostrategic importance of the Maldives.

It would be interesting to see how India-China and US-China geostrategic competition unfolds. What is clear, however, is that things are likely to get much worse for India in the Maldives as Male and Beijing expand and deepen their strategic partnership.

(This article was originally published under Creative Commons by 360info)