Patan is a historical city situated in Lalitpur District of Nepal, inhabited by the people of Newar community. A remarkable characteristic of this city is its portrayal of religious harmony between Hindus and Buddhists in every aspect of the community. Being born and raised here, I got more and more interested in the city when I started doing my graduate studies in Urban Planning, and the insights have been truly fulfilling.

Sustainable cities are the pressing need of modern times. City planners use tactics such as zoning, open space allocation, walkability, urban growth boundaries, satellite cities and many more to achieve this, but the way in which the then planners of Patan achieved this is truly worth learning.

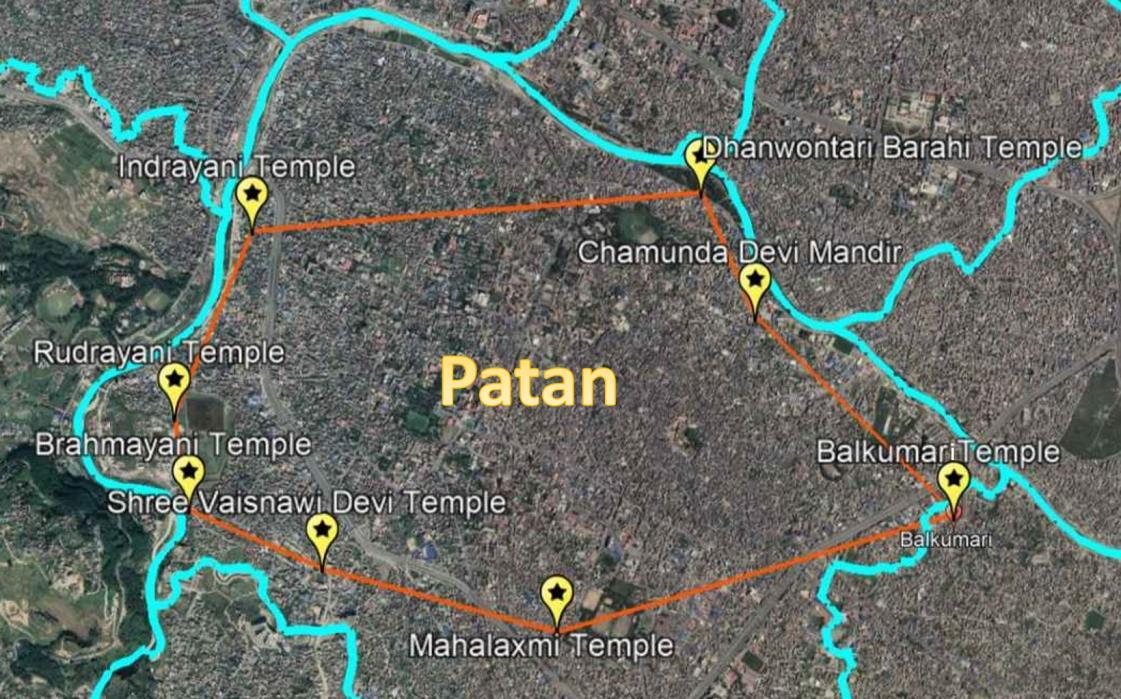

Let me take you through Patan in the 17th century. To start with, “Astamatrika”, the eight mother goddesses, and “Dashamahavidya”, the 10 goddesses, were established to set the boundary for urban expansion. The faith in these places of worship was such that people did not go beyond the perimeter set by the goddesses. This protected the lower fertile agricultural land, while the higher ground was used for settlement. So the perimeter boundary directed the development to be compact, and thus walkable. However, though there was compactness, there were ample urban open spaces and lung spaces (green spaces). Urban open spaces named “Lachi”, “Nani”, “Bahal” & “Bahi” were preserved and each was tied with its respective religious belief system (Hinduism or Buddhism), such that no one encroached upon it (unlike our open spaces!). For lung spaces named “khyo”, different festivals and socio-cultural events were planned such that the space would be in constant care. Also, open spaces of ecological importance were tied with various rituals too. The planners then had the vision and the creative methods to protect these open spaces.

Astamatrika of Patan (Source: Google Earth)

Astamatrika of Patan (Source: Google Earth)

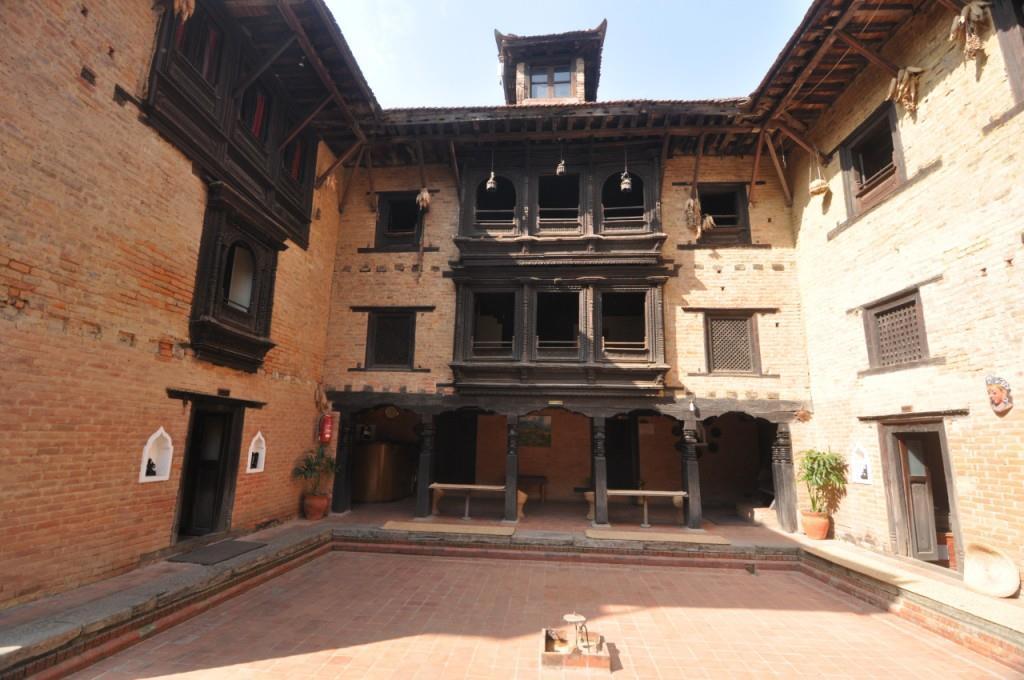

Moving further into the city, the form of residential quarters shows the importance given to communal living. The houses are clustered around an inner courtyard, giving room for private spaces inside houses, while ensuring access to a larger public space for everyone. This model with slight deviations is becoming popular with Western developers too.

Newa Chen, a 17th-century building, renovated in 2006 with help from UNESCO

Newa Chen, a 17th-century building, renovated in 2006 with help from UNESCO

In the case of zoning, it was “zoning by jaat” or “zoning by profession”. Though the concept of “jaat” led to social discrimination, in those days it was primarily used to create “homogeneous communities by occupation” to create agglomeration and economies of scale. With all this in place, when the population still exceeded a certain limit, a satellite town was established with linkages to the main town, to curb the effects of overpopulation.

So this begs the question, how was this extraordinary feat made possible? Certainly, the planners were quite creative and the tool they used was ritual mediation. The meanings given by the people to these rituals had bound the people. They put tremendous faith in rituals and religion. But now, as with every historic city, Patan is going through the process of degeneration. At times the rituals can be seen to be performed only for the sake of rituals, without paying enough attention to the deeper purpose of sustainability, which they hoped to achieve. This situation has brought forth a new set of challenges, which calls for maximum creative efforts by planners to establish newer meanings. An example could be, the lung spaces mentioned earlier being protected through socio-cultural events might be adjusted by giving access to schools for their events in culture and sports, in case the previous ties grow weaker.

History serves as a record of experiences and learning, but not as a rule book. It is up to us to learn from the experiences of the past, and come up with creative solutions to tackle the challenges of the present and future.

May the planners of the future write as highly of us as we write about the planners of the past.